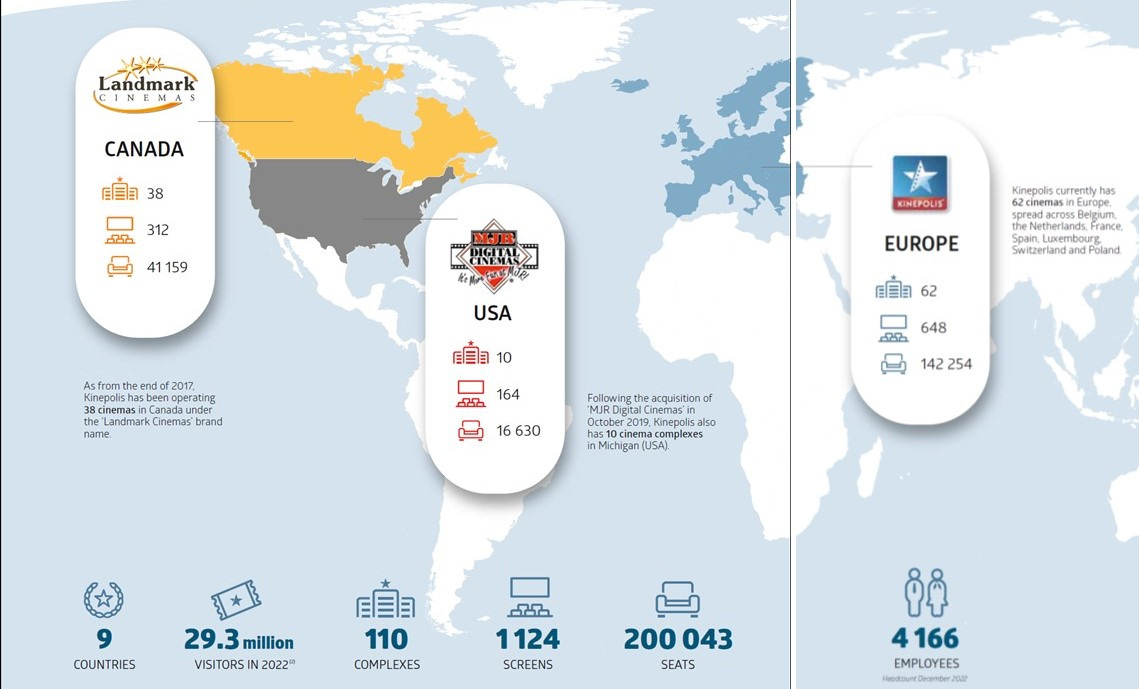

Kinepolis Group NV ($KIN.BR) is a €1.2 billion company that operates cinema complexes in Europe and North America: in total, it currently operates 110 cinemas (51 of which it owns) with 1,124 screens and more than 200,000 seats.

Europe accounts for two thirds of current sales, and North America for the remaining third.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mr Market Miscalculates to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.