“Default: The Landmark Court Battle over Argentina’s $100 Billion Debt Restructuring”

There are dozens of books and papers on Argentina’s default in 2001, but this one stands out as well-researched and clearly explaining the full history of the default and the fight by investors over the following 15 years to be repaid their money. A bit technical at times, but that’s as it should be: in the end the battle between Argentina and the holdout creditors was mostly legal, and only marginally economical.1

I read the book in less than 3 days: mandatory for anyone interested in distressed debt investing, together with The Caesars Palace Coup for corporates. For those interested in the causes that led to the crisis I recommend Paul Blustein’s And the Money Kept Rolling In (and Out).

An abridged history

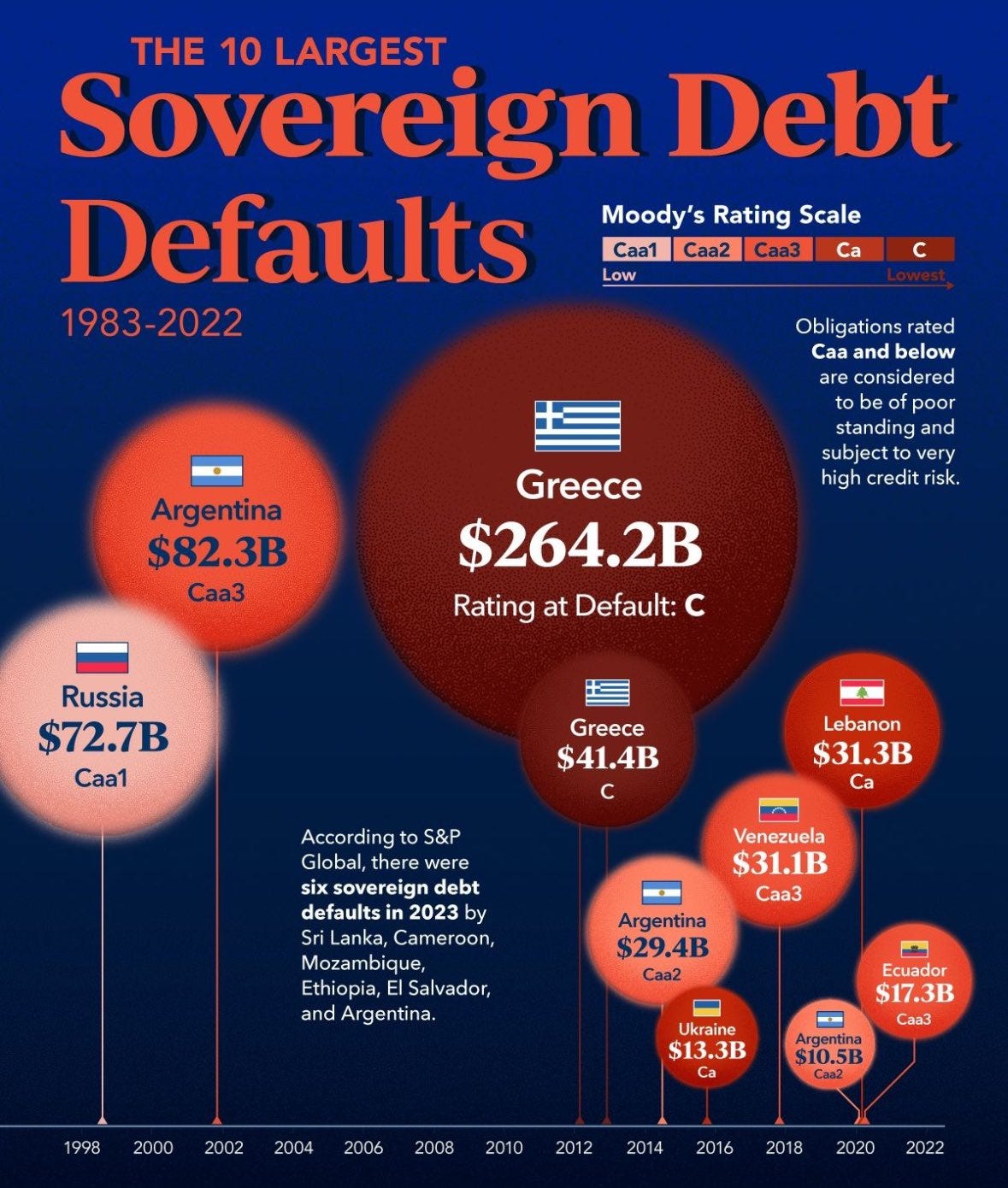

In December 2001 the Republic of Argentina defaulted on over US$100 billion of bonds (roughly US$82 billion of par value and US$20 of unpaid interests).2

At the time it was the largest default ever, although it was surpassed by Greece in 2012 with a total of over US$300 billion; Russia in 1998 (US$73 billion) wins the bronze medal in this Olympics.

What followed were 15 years of legal battles which only ended in 2016 and which tested the theoretical limits of chaos theory, including Elliott Management impounding the Argentinian Frigate ARA Libertad when it was stationed in Ghana!

The book details the disaster story that was the restructuring process, with multiple problems besieging it, some stemming from inadequacies of law and contract, some political, and some that were homegrown.

Argentina did everything it could to live by the anecdote recounted by preeminent financier William R. Rhodes in his autobiography: when the Nicaraguan authorities signed off their 1980s debt restructuring with private creditors, they used a gold pen which had inscribed the phrase: “Firmar me harás. Pagar jamás.” (“You can make me sign, but you’ll never make me pay”).

Following this motto, during these 15 years Argentina managed to antagonise and anger investors all across the world (not just US hedge funds, but especially retail investors in Germany, Italy and Japan), the IMF, the World Bank and several G7 countries. The relationship was more ambivalent with the different US administrations during the time: on one hand, the US Treasury sided several times with Argentina (often writing amicus briefs to the courts in support of its efforts); on the other hand, Argentina did clash with both his neighbours and Washington, at one time even cozying up to Iran.

Just to briefly recap the timeline of the most salient events in a saga that is probably already known (at least in broad terms) to most:

December 23, 2001: Argentina announces the debt moratorium

November 15, 2002: Argentina defaults on a World Bank loan to gain leverage over the IMF on lending conditions

January 24, 2003: The IMF approves a transitional program for Argentina, which indicates that it is seeking a 70% haircut from international creditors on defaulted bonds

May 25, 2003: Néstor Kirchner is sworn in as the president of Argentina

September 22, 2003: in Dubai, Argentina announces indicative terms of its restructuring deal, which shocked investors: old bonds would be replaced with new bonds worth 75% less in terms of face value, with the new bonds carrying very low coupons and long new maturities; the country would also not make up the almost $20 billion of interest payments missed since December 2001. Typical creditor losses had only been half as much in the 1990s, with Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico obtaining debt relief of only 35% in their Brady programs, and investors were expecting similar percentages.

June 1, 2004: in Buenos Aires, Argentina announces improved terms of its offer, still not liked by almost all investors: the revised offer decreased the nominal cut investors would see in their holdings to 66% (from 75%), but coupons remained extra-low, starting around 2% and stepping up to 5.25% over twenty-five years. All participants would also receive GDP-linked warrants which would pay off handsomely if Argentina’s economy subsequently grew at a rate in excess of 3% per annum

August 12, 2004: The Financial Times reports that Argentina is lapsing its program with the IMF until after the debt restructuring is completed

January 12, 2005: Argentina officially launches its offer

February 9, 2005: the country enacts the Lock Law, essentially saying that investors who held out (i.e., do not accept the offer) would never be paid even if they held court judgments

February 25, 2005: Argentina announces that more than 75% of its creditors agreed to accept the offer: many retail investors couldn’t keep fighting and were scared by the Lock Law into accepting

June 2, 2005: the transaction closes with about $19.6 billion of holdout bonds left outstanding

During 2006 and 2007 the holdouts (principally Elliott Management via NML Capital, but also other funds like Kenneth Dart’s EM, Bracebridge, Montreux Partners, Aurelius and funds owned by Yale University) tried – mostly unsuccessfully apart for small amounts - to attach assets owned by Argentina in New York and other jurisdictions, for example the Banco Central de la República Argentina (the Central Bank of Argentina), which were ultimately deemed to be unattachable in the US under the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act (FSIA), which gives foreign central bank reserves nearly bulletproof immunity.

The big events in the saga happened in 2010: first, despite its absolute reluctance to interact with creditors, in April Argentina decide to reopen its 2005 offer on the same terms, which was completed in September leaving less than US$7 billion of outstanding holdouts.

More important, in October 2010 Elliott launched its “pari passu” attack which will ultimately seal its victory. After more legal wrangles, in January 2016 Argentina capitulated and started preliminary meetings with the largest holdout investors: in the following weeks, most settled separately with the country (see below for the terms).

The pari passu clause: the precedent of the Peru bonds

Two things helped the holdouts prevail in the end.

The first was the lack of an “exit consent” in the 2005 restructuring offer.3

“Corporate and sovereign bond restructurings, particularly in the United States, regularly include exit consents to convince would-be holdouts to play nice. Investors who take the offer of new bonds in an exchange offer with an exit consent simultaneously vote to strip protective covenants from the original bonds. Investors are thus compelled to take the issuer’s transaction, because they otherwise risk being left holding a rump of old bonds whose protective covenants have been stripped. From a game theory perspective, an exit consent is a stick. And it’s legal. U.S. courts and regulators allow exit consents to be used even when doing so is commercially aggressive, causing great harm to bondholders who do not accept a deal. The only condition on their use is that the original bond documents permit an exit consent to take place, typically providing a specific list of covenants that may be stripped in a vote.”

It was surprising and not yet clear why Argentina decided not to include this preventative stick against potential holdouts, despite the clause being explicitly discussed in a meeting with Elliott in January 2005 (indicating that the hedge fund was indeed thinking of holding out). It was a regrettable decision.

The second issue that tilted the lawsuits in Elliott’s favour was the pari passu argument, already used by the hedge fund in litigating with Peru in 2000. The Latin phrase pari passu literally translate in English as “in equal step”: Elliott’s interpretation was that it meant “equal payment”, in other words, whenever Peru made a payment to any of its bondholders, it would have to pay all its bondholders any amounts that were due, regardless of whether they had accepted a restructuring deal or held out.4

While a Belgian court accepted this interpretation5, most legal scholars countered that pari passu was about “equal ranking”, not equal payment: ranking obligations and payment obligations are two distinct contractual features of credit instruments, and should not be conflated. An equal ranking clause, they pointed out, prohibits a country from issuing a new bond that is higher ranked than an old bond if that old bond has a pari passu clause protecting its holders. But the exact meaning of the clause had however never been litigated in the US, and the language found in various loan and bond agreements were not entirely clear on their intended meaning.

This ambiguity gave Elliott room to argue that the equal payments interpretation applied to Peru’s and, later, also to Argentina’s debt. Ultimately, probably also thanks to Argentina’s delaying tactics and unresponsiveness to the orders issued by Judge Griesa in New York, the US courts sided with Elliott and the other holdouts.

The final terms

With the courts starting to lean towards the holdouts, presidential candidate Mauricio Macri stated that, if elected, he would settle with creditors. As this happened in 2015, the process was in motion for a final resolution, although it still didn’t go smoothly.

With the national accounts worsening and the Republic cut out of the international bond market because of the holdout litigation, the pari passu ruling (which meant that Argentina couldn’t pay any bondholder if it didn’t also pay the holdouts) effectively forced the country to default again in 2014.

Everyone was very tired after 15 long years, and claimants, seeing an opportunity, rushed to reach separate agreements with the Republic: for example, the roughly 15,000 Italian retail investors remaining in the class action got 100% of the face amount of their bonds plus 50% more to cover a portion of the interest that had gone unpaid since 2001. With minor differences, for the hedge funds the deal (the “Propuesta”) roughly meant getting 1.5 times par plus 70% of accreted value for claims held by creditors who had the benefit of a pari passu injunction, plus a 2.5% premium for investors who took the offer by February 19. That was roughly equal to 75% of the holdouts total claim value, a 25% discount on the full value of the plaintiffs’ most important claims.6

Overall, Argentina could be satisfied with the outcome (at least in monetary terms, probably not in political terms): one noteworthy aspect of Argentina’s settlements was that the country agreed to pay the plaintiffs in cash, rather than with new bonds. They reasoned that they would get a better deal by paying the holdouts in cash and issuing new bonds into the market to fund the settlement: if the country paid the holdouts in bonds, they would demand that they be issued at a significant discount to market value even though most investors were sure that Argentine bond prices would rise upon the announcement of the settlements. Indeed, in April 2016, Argentina issued US$16.5 billion in new global bonds, with the funds used to pay the holdouts and to make up missed payments to exchange bondholders.

The FRAN bonds

One of the most peculiar security in the entire saga was a set of unique bonds: the floating-rate accrual notes (FRANs), an instrument issued by Argentina in 1998. What was so special was that the coupon payment was based on a formula tied to the yield in the market of another Argentine bond: when Argentina defaulted, the yield of that reference bond shot up to 101.5%. Then, for some reason, the agent responsible for quoting the yield of the reference bond stopped publishing new market values, which left the FRANs running at a 101.5% coupon forever.

For investors, it was a dream come true: as of 2005, there was only about $300 million in nominal value of these bonds outstanding, and Elliott and two other investors managed to scavenge the market to buy them all. In time, these investors would obtain judgments of about US$3 billion dollars on their US$300 million of FRANs, ten times the bonds’ face value. However, under the final settlement plan, in round numbers the FRAN plaintiffs got 7x par (versus the 10x par legal value of their holdings).

CAC clauses

Even before the Argentinian default in 2001, policy makers, academics and economists have been discussing for years about the festering problem of sovereign debt restructurings.

One of the ideas put forward (in particular by economists at the IMF) was to set up a new international facility, called a sovereign debt restructuring mechanism (SDRM), to administer sovereign debt restructurings under which the IMF would gain extraordinary new legal powers, including the authority to decide when countries could default and enjoy protection from litigation while they worked out their debts.

The US administration, however, counter-proposed a slimmed-down alternative called Collective Action Clauses (CACs), which would have the sole purpose of preventing potential holdouts from gaming future sovereign debt restructurings by bind majority agreements onto the minority. Under these clauses (to be legally included in the prospectus of new bonds), countries would propose an exchange offer to bondholders: if at least 75% of them accepted it, CACs would give the supermajority the power to force all bondholders into the same deal. So no more holdouts, and no more holdout litigations.

After few years of discussion (and following the default/restructuring of the Greek debt), in September / October 2014 both the Group of Twenty (G20) finance ministers and central bank governors and IMF threw their weight in support for the new CACs clauses.

On October 14, Kazakhstan was the first country to issue US$2.5 billion in new ten- and thirty-year bonds with the new clauses. Shortly after, Mexico (the world’s bellwether EM sovereign debt issuer) also blasted out a US$2 billion ten-year bond with the new CACs and pari passu language. Since October 2014, nearly every single sovereign bond issued around the world has included the new clauses.

But 2016 wasn’t the end of it…

While Argentina’s saga was over by the end of 2016, its debt troubles weren’t. For one, starting in January 2019, the country faced a new wave of lawsuits - including from Aurelius - over selective nonpayment of its GDP warrants. The issue was that in 2014 the country applied a new methodology to calculate its inflation and GDP growth; this change, in turn, reduced the payments on its GDP warrants to less than what some bondholders thought they were owed. This litigation is ongoing at the time of writing of the book.

With Argentina’s economy yet again in crisis, Macri lost the 2019 presidential election to Alberto Fernández, Néstor Kirchner’s former cabinet chief. COVID-19 hit shortly thereafter, putting further pressure on the economy. Argentina defaulted again in May 2020 (“Argentina Tries to Escape Default as It Misses Bond Payment”) and completed the restructuring of almost 100% of its bonds within three months. This quick and clean result was possible because virtually all of Argentina’s bonds included CACs that provided for aggregated voting, protecting the transaction from disruption by holdouts.

Conclusions

Everyone will likely have her personal opinion: it is fair that countries must do whatever they can to repay their debts (which usually involves cutting social spending, selling national assets and/or raising taxes)? Or is it unjust that vutures can profit from the misery of people?

Argentina’s 2001 default will long be remembered as the lengthiest, messiest sovereign debt restructuring in history. And it begs the question of who or what was to blame: was it Argentina’s fault? Was it the fault of the hedge funds? Or was it the lack of a sovereign bankruptcy law?

The saga evolved in three acts:

The disputed and controversial 2005 exchange offer

The litigation phase through 2010, and

The litigation over Elliott Associates’ pari passu claim through the 2016 settlement

While the 2005 exchange offer was largely successful, it also angered many of the protagonists, including the IMF, leaving the legal claims brought by the holdout creditors.

The second phase was a long and exhausting legal battle by the creditors to somehow attached any of the Argentinian assets held abroad, with only a few marginally successful, which set the stage for two-thirds of the holdouts to accept Argentina’s reopening of its deal in 2010 (in the end more than 92% of claimants ended up accepting it). During this phase, Argentina however “abused” of the protection afforded to sovereign states and central banks and removed assets from the US, further angering the US courts.

The final phase was another long legal battle, which this time was resolved in favour of the holdouts, mostly because the Republic’s actions convinced the judge that it was showing no real willingness to settle with its creditors.

While still much criticised, the basic financial structure of Argentina’s 2005 offer made sense: Argentina sought a pro forma level of debt that it could safely pay, and the GDP warrants were an effective mechanism for sharing any upside with creditors. Indeed, the warrants paid out when Argentina’s economy rebounded, just as the country had promised they would even though the deal’s critics called them worthless at the time. The deal was also supported by six international banks that did their own analysis of the country’s capacity to pay. It was a hard deal, but it was not a thoughtless or arbitrary one.

The deal’s biggest problems were political and institutional. Argentina’s politicians (first among them Néstor Kirchner, who was elected in 2003, and then his wife Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who was first elected in 2007 and then confirmed in 2011: Néstor Kirchner passed away in 2010) chose a very populist stance (I don’t want to say machismo but you get the idea): they were dead set from the beginning on fighting the vulture funds (see the Lock Law mentioned above) and always chose the minimum payment to creditors among the options they were presented.

On a purely technical level, Argentina’s deal was unusual in many ways, including the price-match guarantee7, the Lock Law, the powerful GDP warrant, and the lack of an exit consent, with Argentina’s lapse of a relationship with the IMF behind some of these irregularities. The complexity of the deal also had a cost: in retrospect, Argentina put too much potential upside into its complicated GDP warrants, instruments the market undervalued at the time of the deal. Immediate post-transaction commentary from independent experts said that Argentina should have paid a bit more to reduce its contingent liability from the holdout bonds (although the reopening of the deal in 2010 was a critically important operation that substantially reduced the size of the country’s contingent liability from the holdout bonds, saving many billions of dollars for the country).

Overall, the book is less about Elliott and the other hedge funds, and more on sovereign debt law and contracts. Elliott’s prominence in the story, however, shows that the firm is a legally savvy investor, smarter than most: it won in courts because it prosecuted its cases efficiently, effectively, and with great energy. For investors, the book provides a healthy reminder to read the terms of one’s bond documentation. It is a toss-up, however, as to whether the firm beat Argentina or whether the country defeated itself by being so uncooperative.

The author is a physicist by training but worked as a banker for 21 years, when he advised companies, financial institutions, and countries regarding their debt. He also worked as a senior policy adviser at the US Department of the Treasury before moving to the Centre for International Governance Innovation, a think tank based in Waterloo, Ontario.

A 2013 report written for the US Congress details the exact amounts as US$81.8 billion face value of debt plus $20.8 billion of past due interest (PDI). At the time of default Argentina was paying coupons on its global bonds between 10.75% and 19.65%: the roughly $20 billion in PDI is the cumulative amount of missed payments until September 2003, when Argentina presented the first restructuring offer.

A second notable absence in the documents was the lack of a support letter from the IMF, as it happened in prior deals for Ukraine and Uruguay: these letters are especially helpful to convince retail investors that the deal is not a “rip-off” and a “scam.”

If Peru made a payment on its performing Brady bonds, issued in its own restructuring, it would also be obliged to pay any amounts due on the defaulted Peruvian loans Elliott held.

The suit was filed in New York and London because Chase Manhattan Bank, the paying agent for Peru’s Brady bonds, had offices in both cities, and in Luxembourg and Belgium because these payments were due to go through clearing systems in the two countries. Elliott needed to frustrate only a part of Peru’s payment to force the country into a corner: missing even a portion of the amount due would be a default event under the terms of Peru’s Brady bonds.

Under the agreement, Argentina would pay the hedge funds around $4.4 billion against their legal claims of $5.9 billion. Argentina also agreed to pay an additional $235 million to cover the plaintiffs’ legal fees.

The price-match guarantee meant that if Argentina settled with creditors at 34 cents on the dollar in the 2005 transaction but subsequently offered holdout investors 50 cents, the country would have to pay the 16 cents difference to the investors who had accepted the initial 34 cents. As this clause lasted for 10 years and expired at the end of 2015, Argentina was not willing to negotiate with holdouts (despite the insistence of the New York courts) until early 2016, or it would have had to pay the difference to all bondholders.