I’m not a macro investor (I’m bottom-up and not top-down) and I almost never take decisions based on the outlook for interest rates, GDP growth, the price of oil or other macro variables. But I’m macro aware, in the sense that I do check the economic (and geopolitical) situation around the globe.

And a couple of weeks ago I listened to this very interesting online discussion between Russell Napier and Charles and Louis-Vincent Gave of Gavekal Research: “Will China Change the Global Monetary System and How?”

At times the debate resembled a methodological clash between the Gaullist dirigiste economic approach and the Anglo-Saxon laissez-faire, but it did cover the key ground and differences for some of the most important global financial considerations for the years ahead. Definitely worth a full watch!

A long post.

Russell Napier

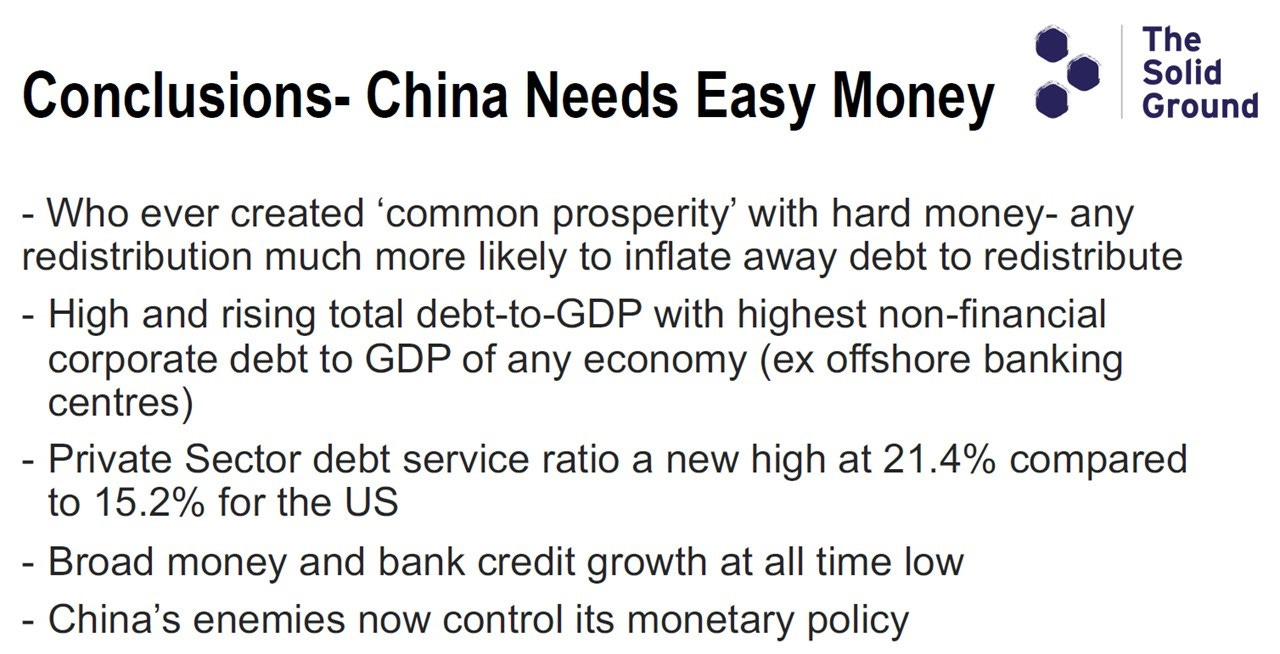

If ever a country needed a solution to a debt problem, it is China. While other countries have begun the process, with an inflation ambush that has boosted nominal GDP growth while materially reducing the price of debt, China remains stuck in a debt trap, which was a long time being set.

Professional investors across the globe fear a form of debt deflation from which the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) cannot provide relief.1 That China is facing a debt deflation is not contested, as it is one of the world’s most indebted countries. The key question is what policy options will be chosen given the growing risks. Napier does not actually expect a debt deflation in China, but investors need to prepare for the policy responses that will prevent such an event and bring a reflation in the economy.

Nothing of course is straightforward and in China’s case there are reasons to think that the political economy of the country might result in the CCP preferring a debt deflation to a reflation: many believe the current situation is being engineered by President Xi in pursuit of his political goal of more control of the levers of economic power, given that he seems to have secured complete political power. As the CCP owns the banking system, a debt deflation is likely to create a scale and nature of default that will see creditors, primarily the state-owned banks, taking control of private sector enterprises.

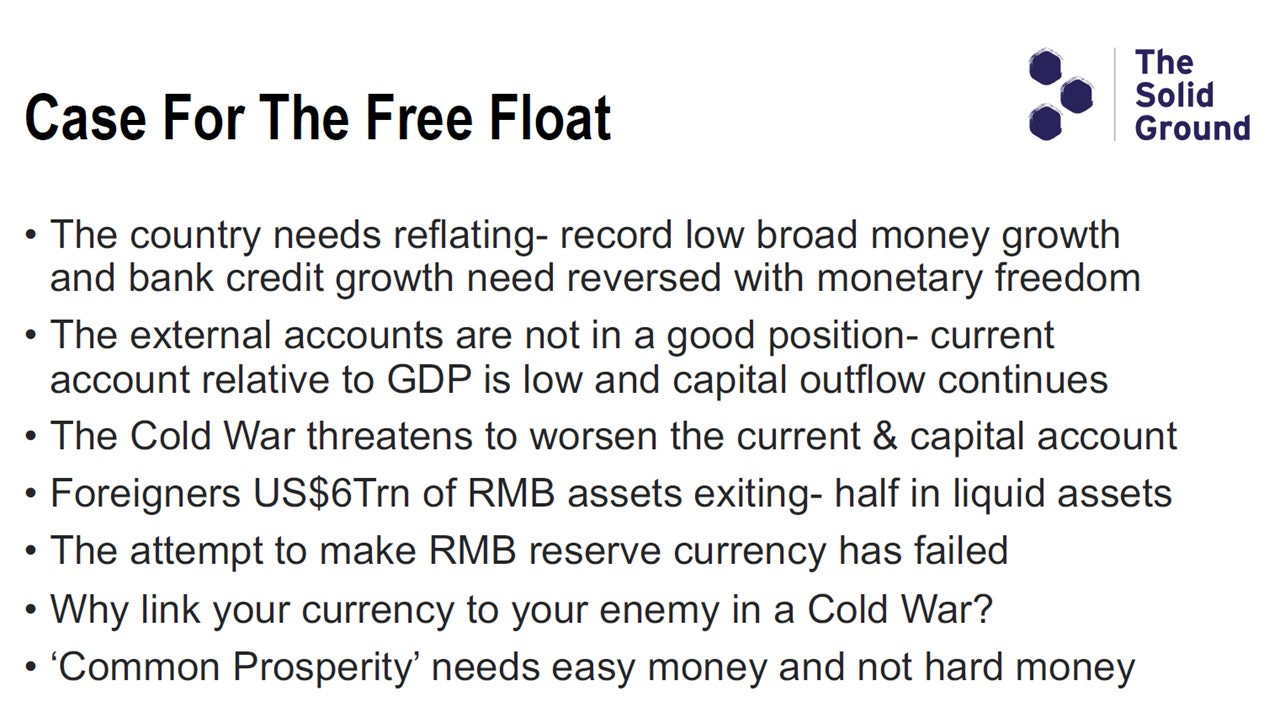

But Napier doubts that XI will push for so much instability and uncertainty: China is indeed about to reflate its economy, but the only way to do it is to abandon the currently managed exchange rate and adopt a free floating exchange rate (likely at a lower level, something he also discussed in this FT article: “China is moving towards full monetary independence”)

“The world’s second-largest economy is about to move to monetary independence and in so doing it will destroy the current international monetary system. China needs to not just reflate its economy but to inflate away its debts.”

“PBoC (People’s bank of China, China’s central bank, ndr) action to accelerate the growth rate of broad money and generate higher growth in nominal GDP is not compatible with a stable exchange rate, especially in an era when trade and capital flows are shifting away from China as part of US “friendshoring”. It is time for China to find a different and fully autonomous monetary policy.”

This is not something that is openly and frankly debated in the investment community: investors should expect Chinese policymakers to follow Irving Fisher’s prescription for ending a debt deflation and the current monetary orthodoxy to end. The Chinese authorities will create more money to inflate away the country’s excessively high debts. In adapting this monetary stance they abandon any attempt to target the exchange rate and the RMB devalues.

This means that China will become a sovereign country, in the sense that having a fully independent monetary policy will allow it to control its interest rate and target the quantity of money in circulation entirely independently.

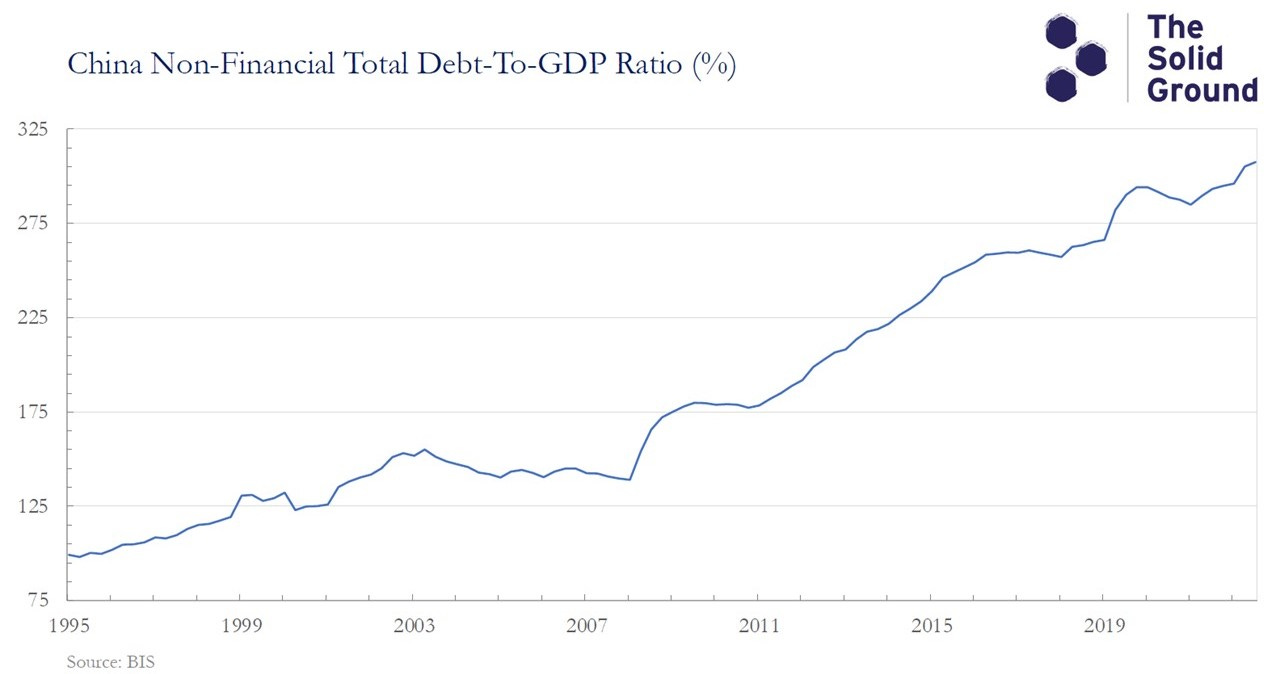

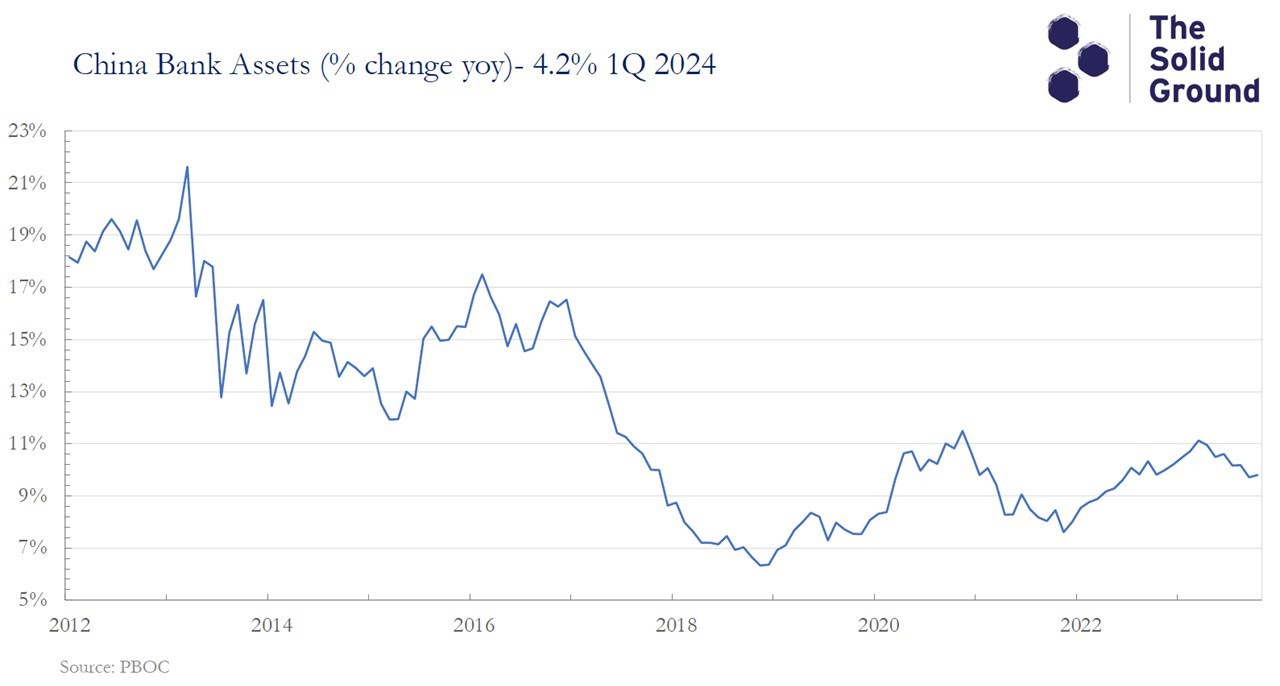

If the PBOC is shackled to a strict exchange rate targeting regime, the growth in local currency liabilities (the liquidity it provides to the Chinese commercial banking system) is very closely tied to the growth in its foreign currency assets. The PBOC does not operate such a strict policy, but this is not to say that it ignores the RMB exchange rate when determining the size of its balance sheet. Chinese monetary policy has been too tight because the PBOC is constrained in determining the appropriate price and quantity of RMB as these variables are basically the residuals that result from a focus on exchange rate targeting. The consequence from the focus on exchange rate stability is that the economy has been expanding fuelled by non-bank credit, and the debt-to-GDP ratio of China has thus risen. In short, the focus on the exchange rate has produced a too low growth rate in the central bank balance sheet and, through its impact on commercial bank balance sheets, too low a growth in broad money and nominal GDP (even in a state-run banking system). At a time when almost all other countries have adopted monetary policies to reduce their total non-financial debt-to-GDP ratio, by expanding the supply of money and boosting nominal GDP growth, China’s debt-to-GDP ratio has continued to rise.

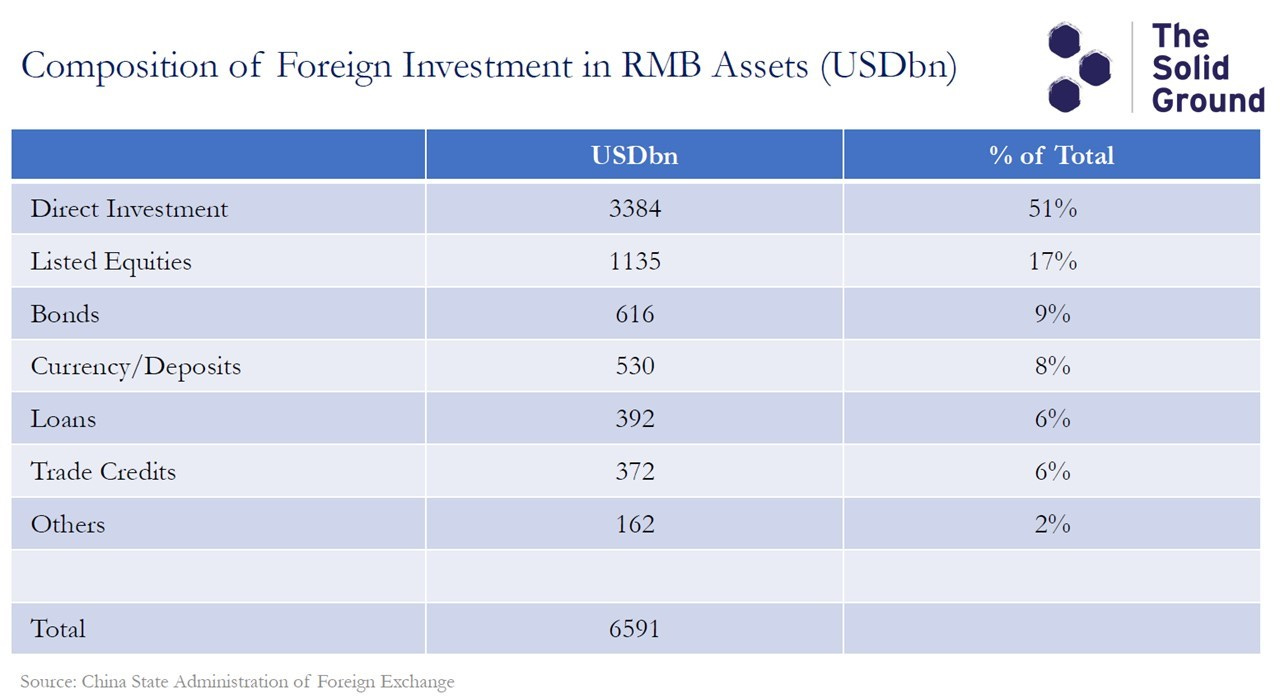

In addition, China’s external accounts are not in a good position (more the capital account than the current account), and the “new Cold War” threatens both. Today foreigners own more than US$6 trillion of RMB-denominated assets, half of which are liquid: for the first time in China’s history there is a possibility at least of a large liquidation of domestic currency denominated financial assets.

In 2009 the US approach to implementing Irving Fisher’s prescription for ending a debt deflation was for the Fed to create new money to offset the destruction that resulted from a contraction in commercial bank balance sheets. The PBOC can do the same by buying RMB denominated assets with newly created RMB. This would almost certainly entail buying Chinese government bonds from financial institutions and the cash created would, as it did in the US from 2009, be reinvested into other liquid assets - most likely equities. The authorities might however conclude that this form of monetary easing would create a form of reflation which favours the owners of existing assets and does not promote Xi’s ‘common prosperity’.2 If the aim of Chinese policymakers is to avoid greater inequality of wealth, it would be better to follow a form of reflation not immediately available to the US authorities in 2009.

As the CCP ‘owns’ the commercial banking system it could insist that the bankers lend money at cheap rates, the form of reflation followed across the developed world in 2020: this put money into the hands of people who would spend it mainly on goods and services and when they were able to do so freely, when lockdown ended, they did so. The impact from this form of reflation was very different from that which followed QE. The growth in commercial bank credit produced a high level of growth in broad money and that money was in the hands of the public and not savings institutions. What followed was a pick-up in real economic growth but particularly a pick-up in the rate of inflation. The ‘surprise’ inflation has produced a major decline in the developed world’s debt-to-GDP ratio. Ownership of the banks allows Xi to press this particular button at any given time to bolster growth and reduce his debt-to-GDP ratio.

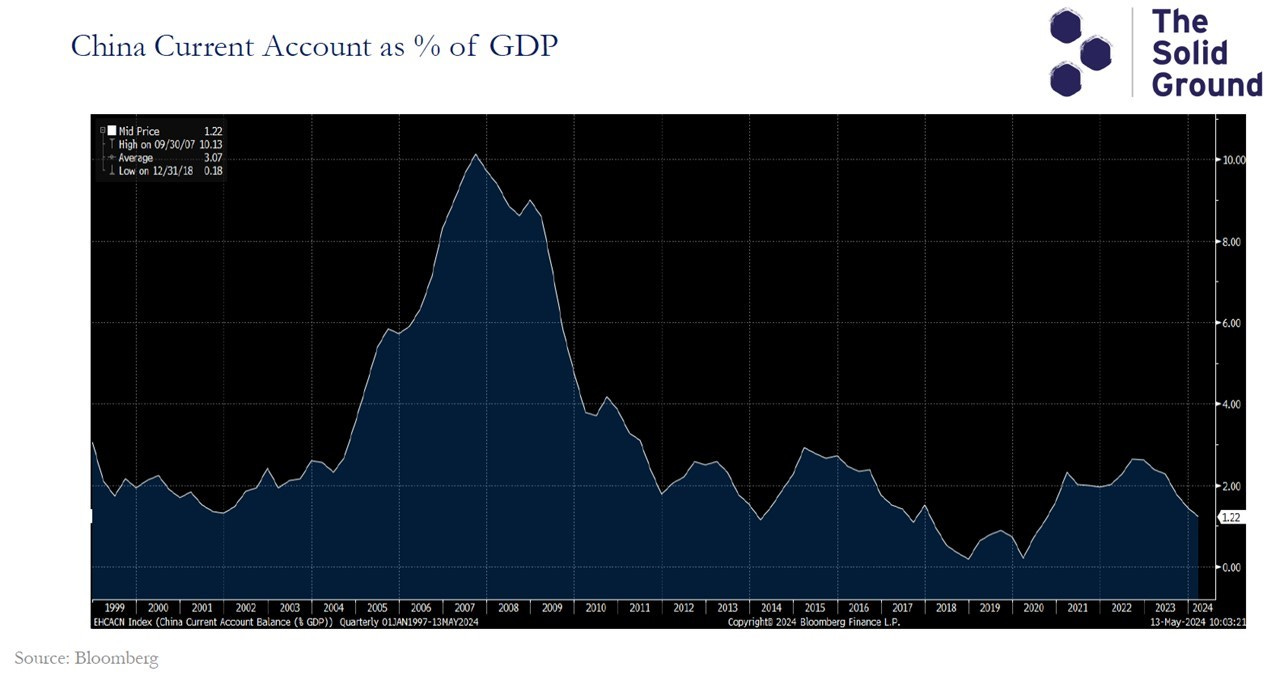

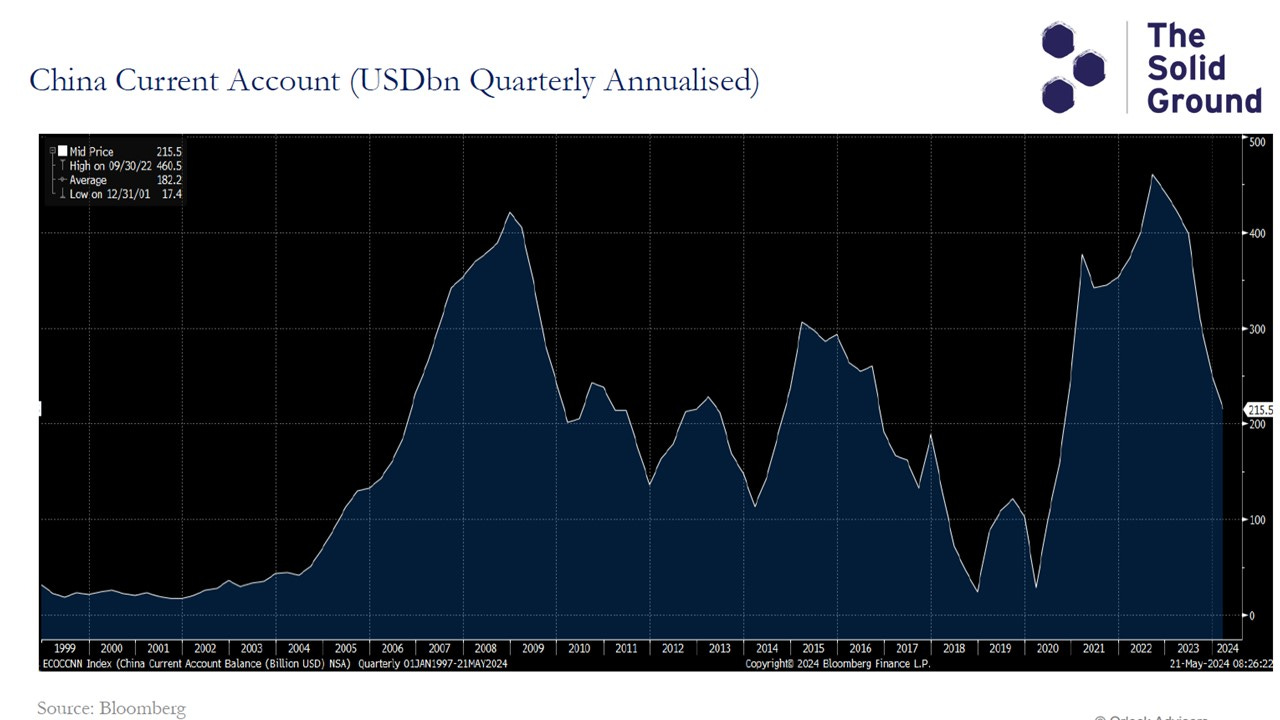

This is where China is on its external account.

Current account surplus is 1.2% to 2% of GDP, at the bottom end of its range since the late 1990s: it might still be large in dollar quantities, but it feeds through into its monitoring flexibility and its ability to run a managed exchange.

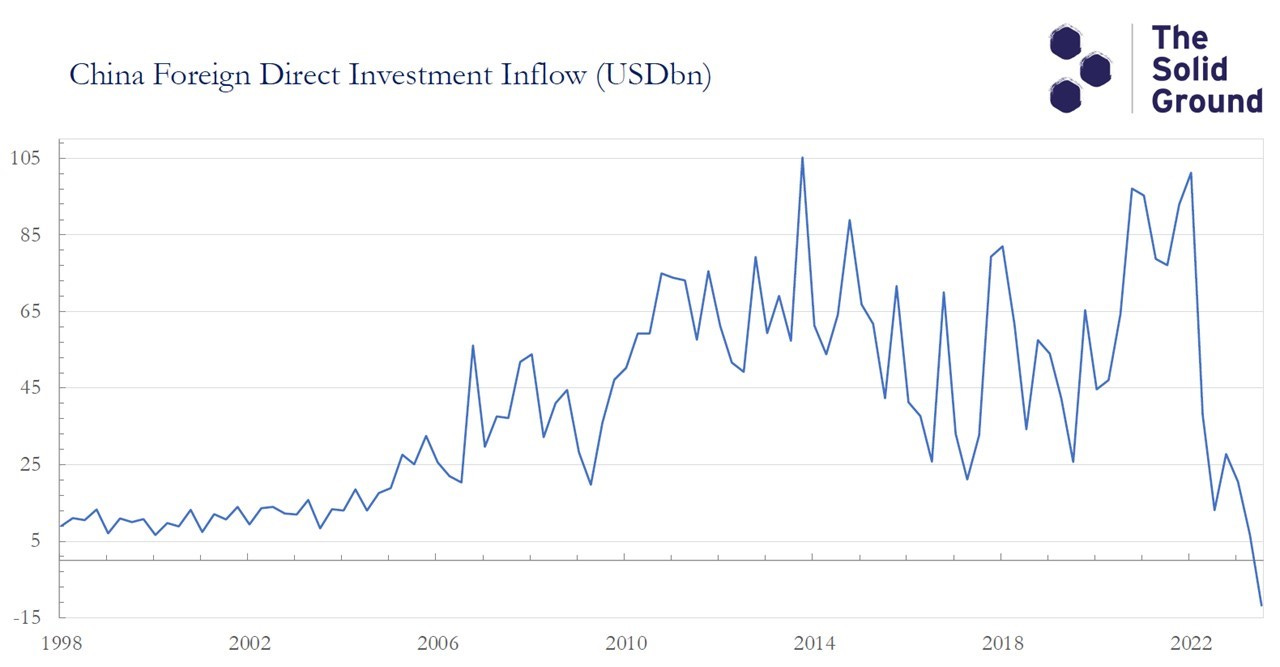

The managed exchange rate might be unbalanced, but it is not going up: rather, it’s coming down. And the reason has to do with Cold War. Chinese FDI inflows have been robust for many many years, but no longer.

In the chart FDI inflows are at 1% of GDP, with the newly released numbers it’s negative: FDI have disappeared, and Napier argues this a Cold War structural dynamic rather than a cyclical dynamic.

All of this feeds into the question: how do you manage an exchange rate and reflate an economy if you have a deteriorating external account (focus is on the capital account but the current account is not good either)?

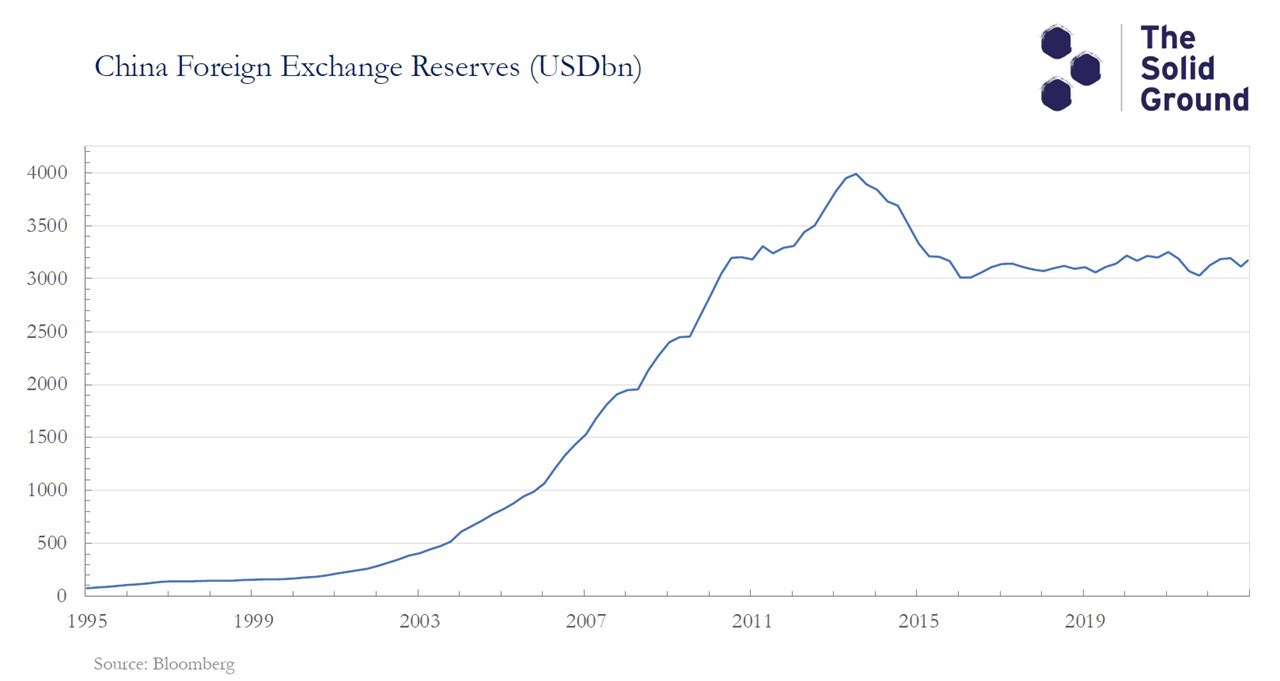

Here is the acid test: foreign exchange reserves have not been going up for a long time, while Chinese debt to GDP really started going up from about 2014. The structural problem China has had for a decade is too much growth in non-bank debt and insufficient growth in money. And the failure to create money is linked to the condition of the external accounts. And the fixation on managing in some way the exchange rate.

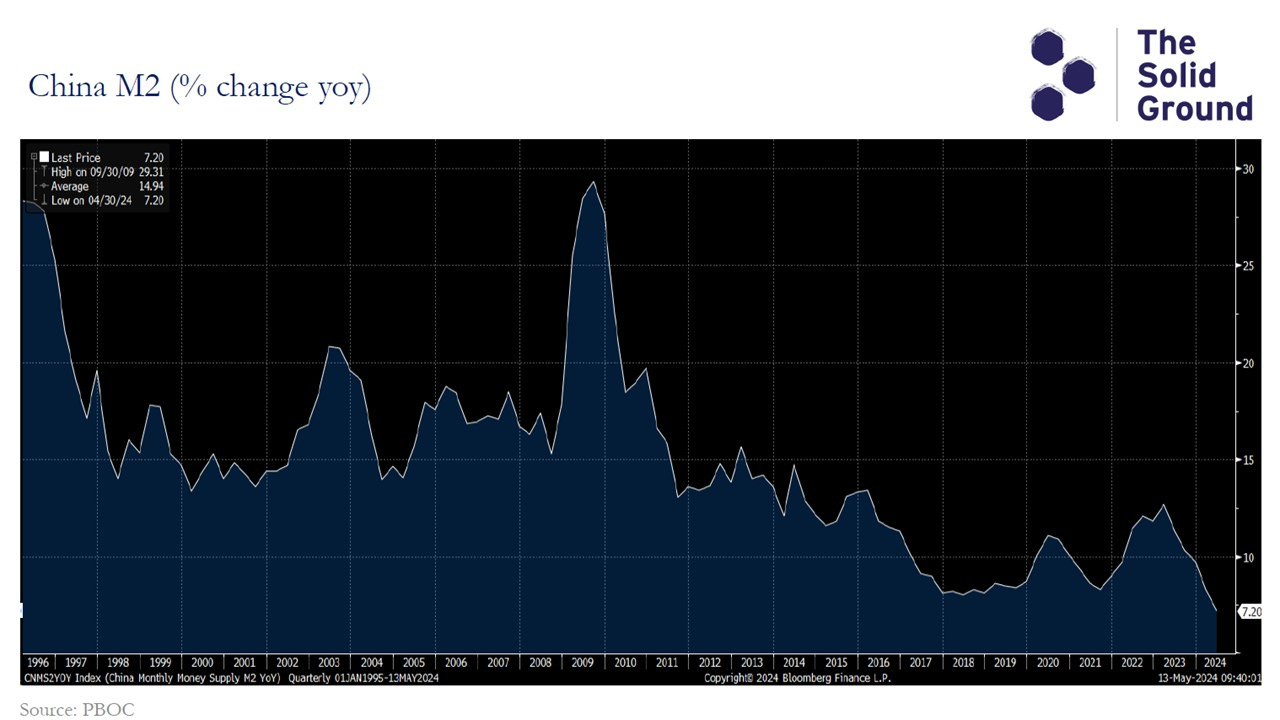

M2 growth speaks for itself: once again, going back to 2014 is when we see the real lift off in debt to GDP and that is when the growth of money goes to new low levels.

China needs higher growth in broad money to grow properly without the risk of a credit crisis and it is simply not achieving it. To achieve it, it needs a truly independent monetary policy: it doesn’t need one hand tied behind its back worrying about the fx.

So the time has come. If anything points towards a need to do something, it’s now, not next year or the year after.

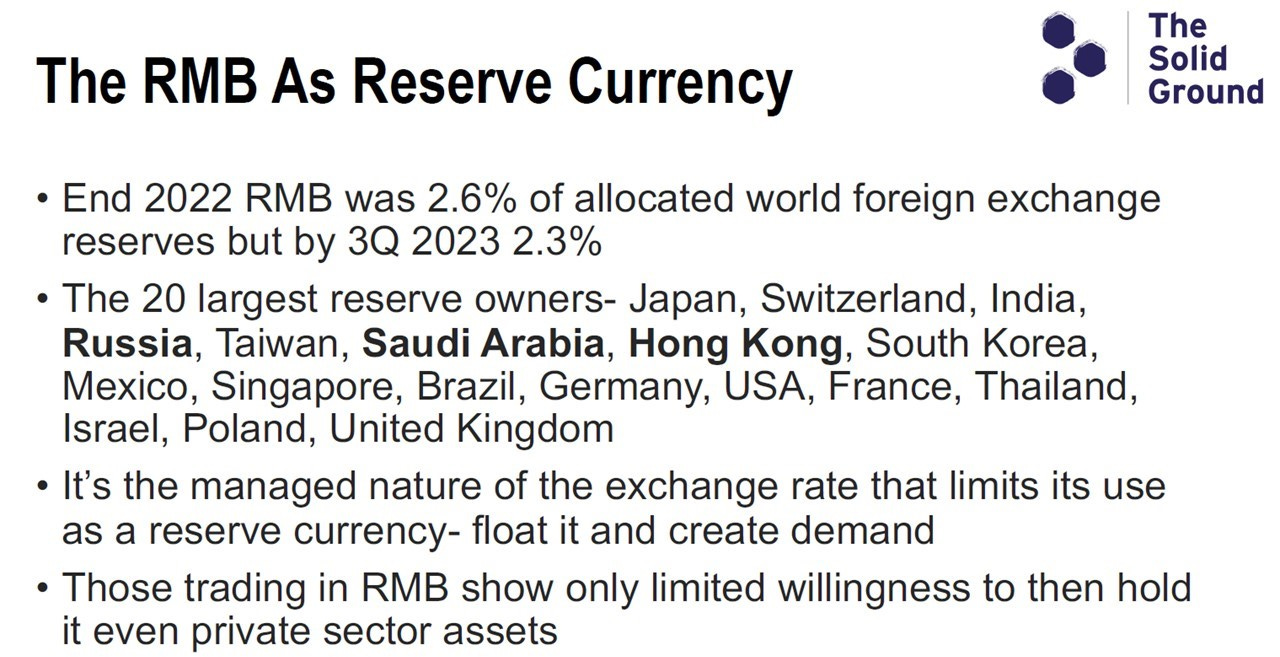

The attempt to make the RMB a global reserve currency has failed: why would you link your currency to your enemy in a Cold War? RMB was 2.6% of allocated global foreign exchange reserves at the end of 2022 and it’s 2.3% now.

Putin owns nearly all of that (although we don’t know exactly how much). But it’s not working for China: getting people to transact in your currency is not the same thing as getting them to hold it. So failure so far doesn’t mean failure going forward, but so far it’s a failure.

Take the list of the 20 largest owners of foreign exchange reserves: in the world we live in, which of these countries is going to diversify from whatever the current holdings are into RMB? The answer: Japan no, Switzerland no, India no, Russia yes (but they already did it to the extent that some reserves are frozen), Taiwan no, Saudi Arabia question mark. The Saudis signed a new deal with the US recently, an enhanced bilateral cooperation on defence, civilian nuclear energy and future technologies; and given the support China is giving to Iran it seems unlikely that they will hold RMB. Not that they would not transact in RMB, but would not hold them: there are little indications of large acquisitions by Saudis in China, either as direct investments or other portfolio assets. Ultimately, if they are going to hold Chinese government bonds they would be funding their enemy in Iran. So Saudi Arabia is not going to do that.

Hong Kong definitely yes, and Napier believes that China will attempt to re-peg the HKD to RMB so that they can get $480bn.

But for everyone else on the list the answer is no: people have different opinions and that could change, but virtually none of the largest owners of foreign exchange reserves in the world are going to hold RMB as a reserve currency for geopolitical reasons.

Still, China needs to create more money. Its debt-to-GDP ratio is one of the highest in the world at 311% (US is at 254%, UK at 230%). Few countries in the world have a higher level than this: Japan is one, France is the other. It is difficult to divide it between the government and the corporate sector, but the BIS does it: China’s corporate debt to GDP is 167%. For comparison, the US is at 78%, and that’s the highest level ever in its history.

China is the only country in the world (according to BIS) with a rising debt-to-GDP ratio: every other country has it coming down because they have high nominal GDP growth and a falling bond price (i.e., the price of debt is declining).

China is now one of the world’s most indebted economies, but it wasn’t always so. On the eve of the Global Financial Crisis its total non-financial debt-to-GDP ratio was just 143%, low compared to the advanced economies average level of 243% and 226% for the US. China’s private sector debt service ratio (the percentage of private sector income needed to service debt burdens) was 13% in 2007, well below the 18% level of the US. What then followed was one of the greatest investment booms ever recorded as China sought to avoid the impact of the GFC upon its economy. This was almost certainly the greatest peacetime malinvestment ever seen.

Something will be done about this, and that needs monetary policy independence through a flexible exchange rate. The basic argument here is that at some stage most world leaders have to choose between the stability of the exchange rate or the level of interest rates. Think about Lord Lamont (UK chancellor of the exchequer) in 1992: he concluded – quite correctly – that it was more important to control the price and quantity of money than to control the exchange rate.

This is even more so in a Cold War. If through sanctions and capital restrictions America and its allies can control the condition of your external accounts, it is exceptionally dangerous to give them that option. If you have a flexible exchange rate, you certainly give them the option to manipulate it; but with a free-floating rate you can still control the level of interest rates and the quantity of money. And if you see your external accounts now used as a weapon against you, you can neutralise it at least in terms of monetary policy, by going to a free float.

Here are the numbers for the current account: it’s not growing.

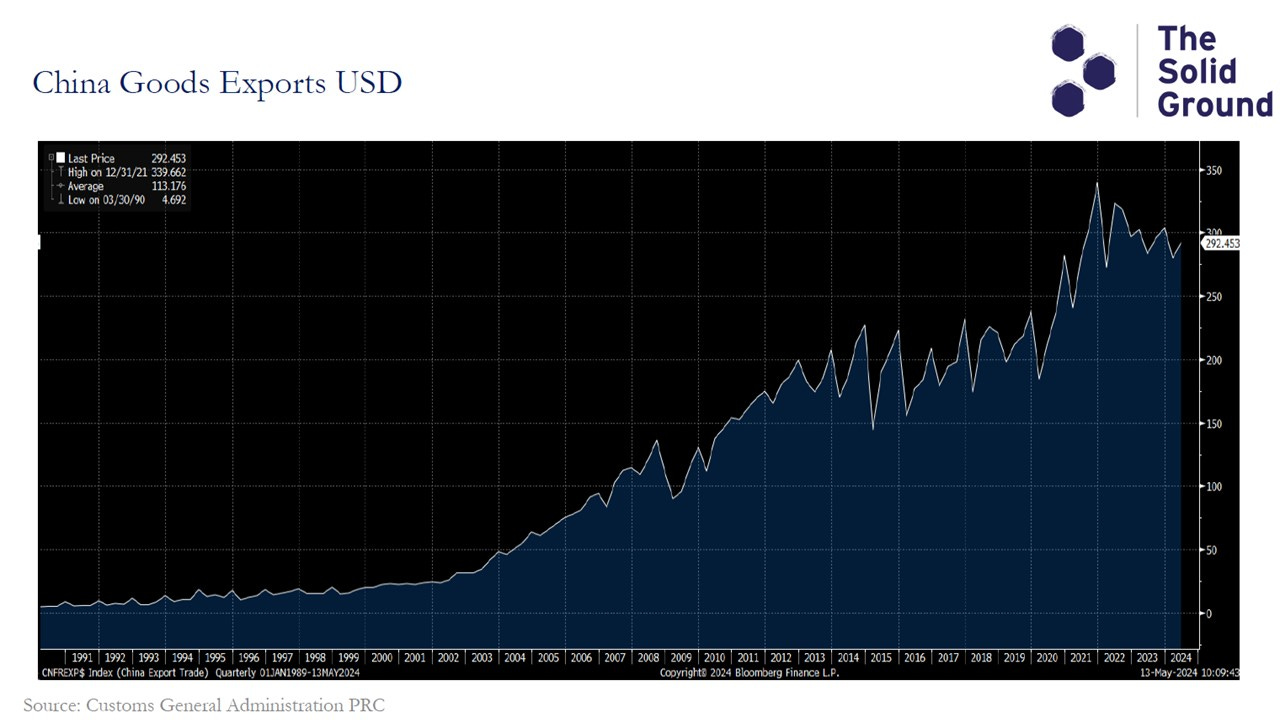

And here are the exports in dollar terms (not radically different if you do it in RMB): Napier’s argument is that the recent decline is structural. The trend didn’t change with Covid, it changed with the invasion of Ukraine and is related to sanctions and tariffs. So there’s a strategic structural problem in terms of exports.

The reason that the trade account is still okay is that there is no more growth. We know from the statistics that the Chinese economy is still growing at 5.4% real (pretty spectacular), but not in imports: the explanation to partially help the external accounts may be the suppression of domestic demand.

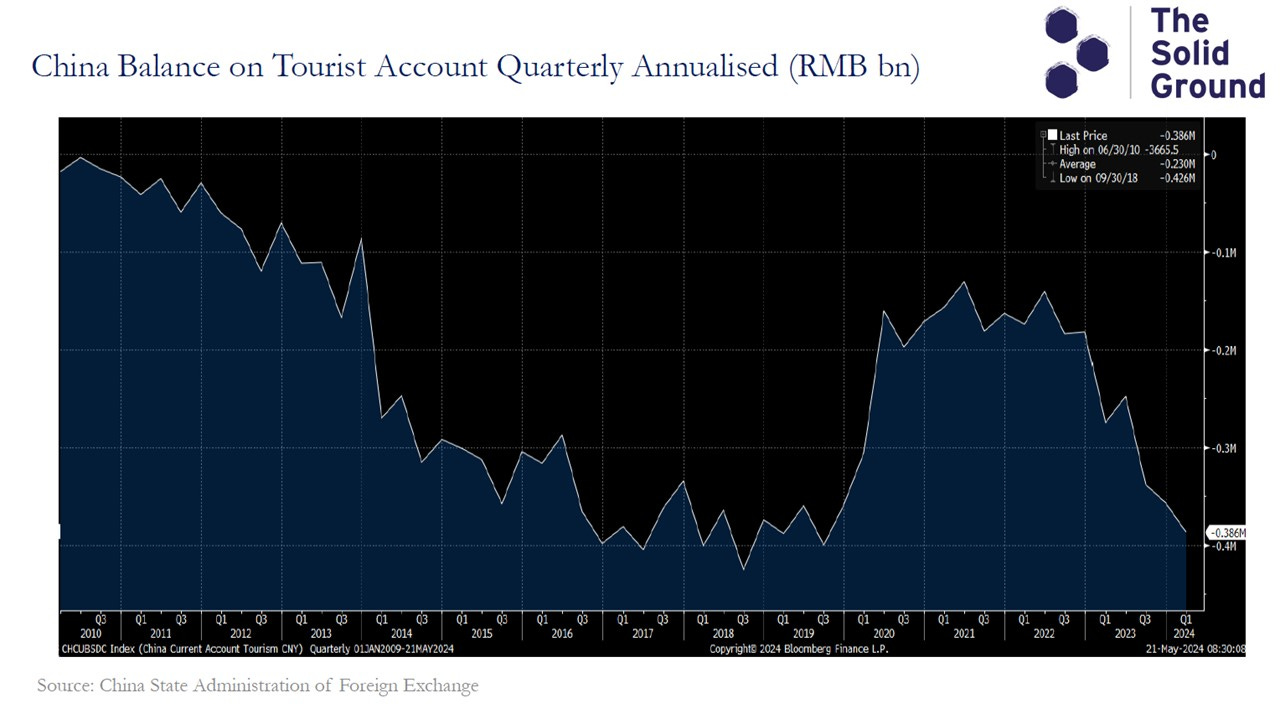

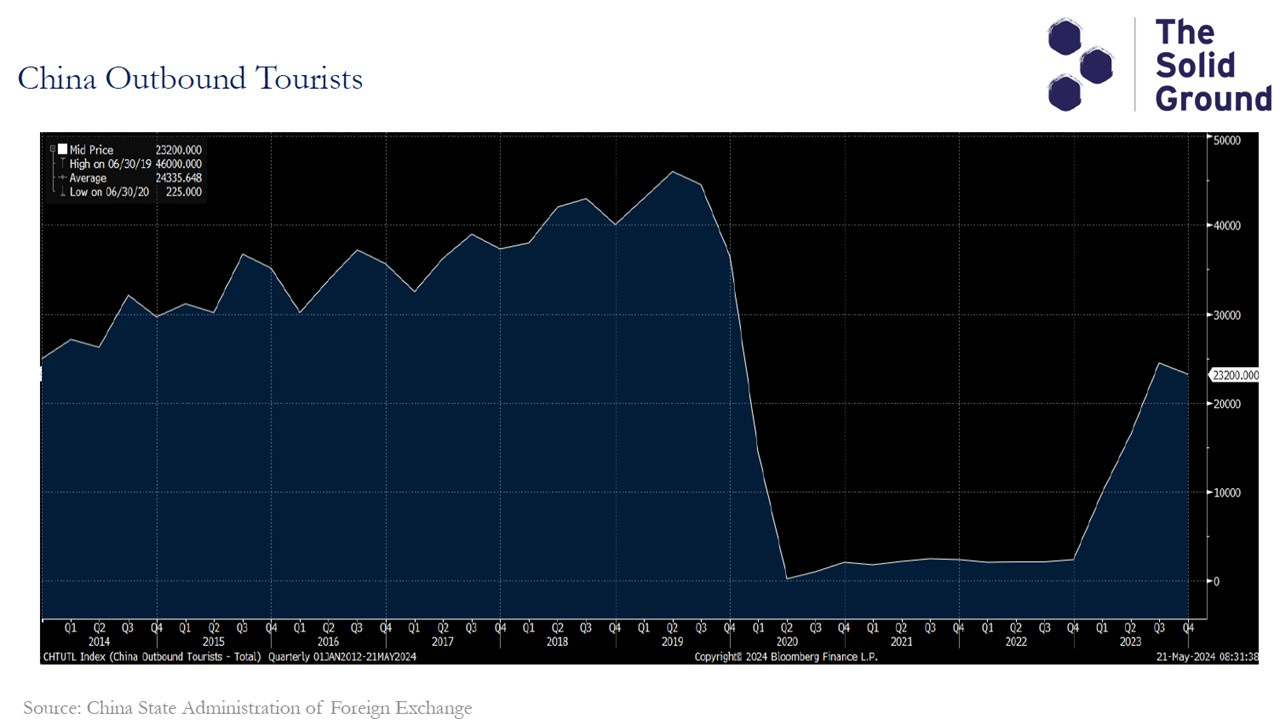

The tourism deficit is escalating rapidly as it can be seen in the following charts: it is nearly as bad as it ever was. Unfortunately, it’s not driven by the number of tourists; the number of Chinese outbound tourists picked up last year but it’s still roughly half its peak. And yet the deficit is almost on a record high: the Chinese are spending more money abroad than they have ever done. It’s driven by something else: somewhere in this tourism numbers there is a hidden capital outflow.

It will get worse in a Cold War: capital is leaving, it’s not coming in. This are the FDI flows.

Latest numbers for FDI inflows are negative, very rare thing to see. China’s great success over the last 25 years was not just running a current account surplus, it was also running a huge capital account and massive FDI inflows. And it’s not getting them now. Once again you have to ask the question: structural or cyclical?

Napier’s answer is that it’s structural: we’re watching one of the most rapid realignment of supply chains in human history, which is not going to rebound quickly.

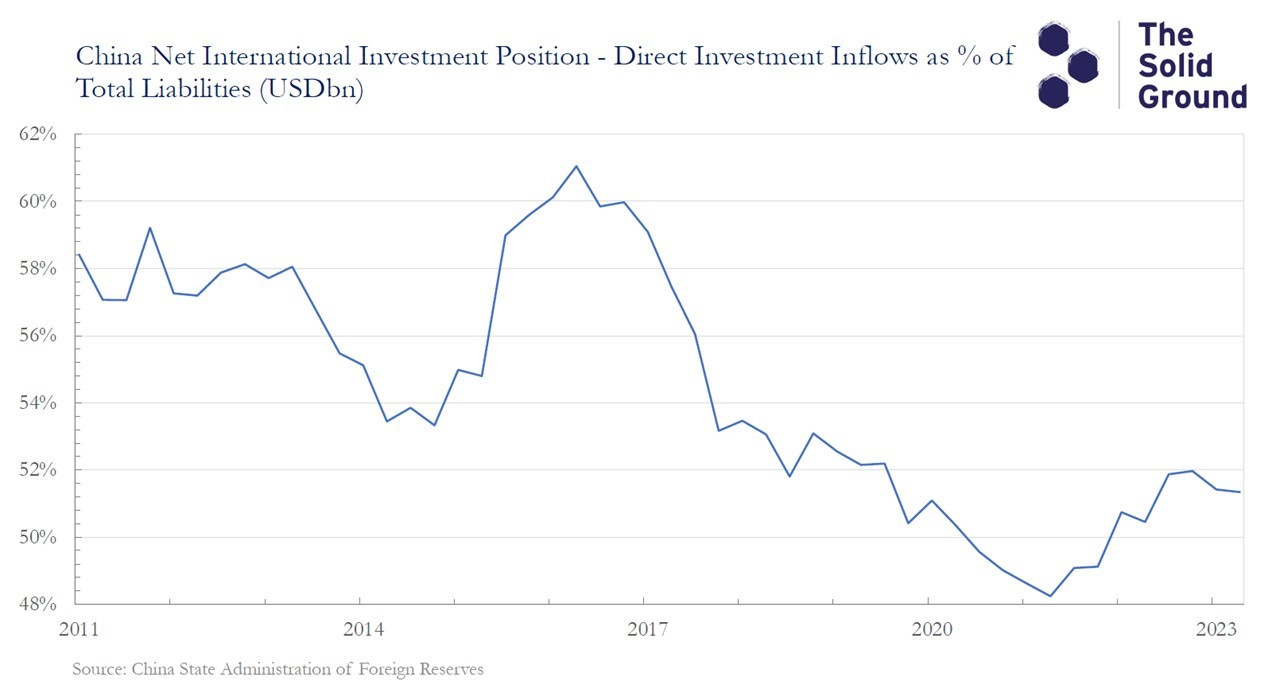

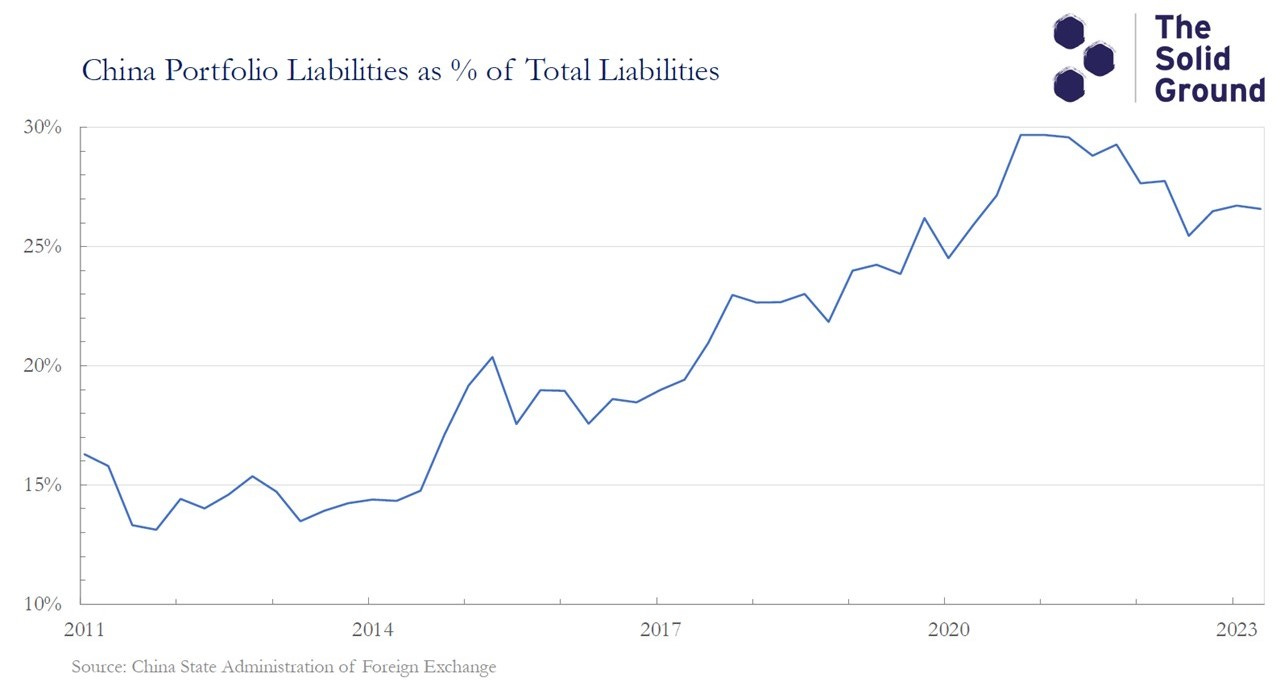

Not only that: a higher proportion of Chinese capital inflows are portfolio flows, and not direct investment flows. In the good old days, it was dominated by foreign direct investments, which are very sticky: once they are in, they tend to stay.

But as we have experienced several times, particularly in Asia in the mid-nineties, if you get lots of portfolio inflows, they can obviously go the other direction: these flows can come in, then go out and they don’t have to be driven by economics. They can be driven by geopolitics. It could be a geopolitical thing that forces foreigners to stop putting portfolio capital in China, and maybe bring it out.

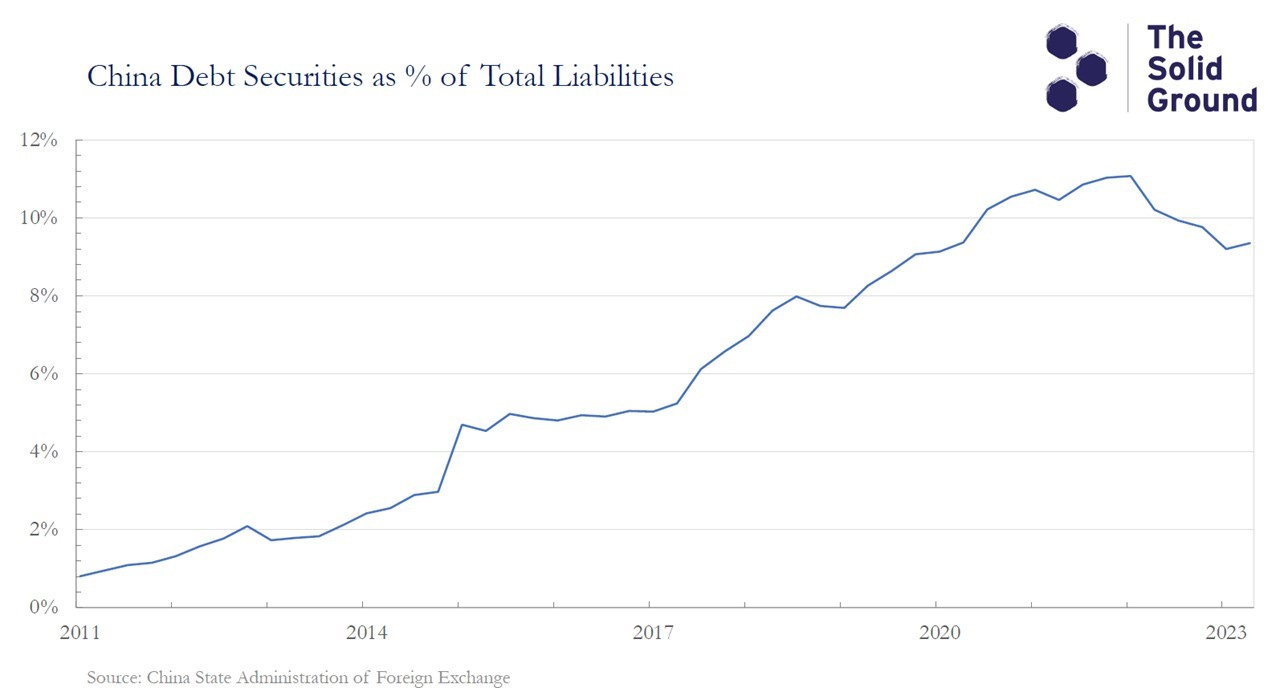

The next charts show huge portfolio surpluses associated with the purchase of bonds (more than equities) when the Chinese bond market was open to foreign investors. Today, foreigners own over $600bn worth of RMB denominated bonds. That’s enough to build 52 aircraft carriers: if one was of a mind to be mischievous in Congress, one could point out that global savers are building 52 aircraft carriers for the Chinese state. Chinese debt securities as a percentage of all the assets foreigners have has increased in a decade from virtually zero to over 10%. Including both equities and bonds we get to over a quarter of all the assets that foreigners have in China in this very liquid format which could come out. It seems unlikley that the western world will permit foreign savings to fund the CCP in a Cold War and that huge inflow associated with bonds won’t be replicated.

Here are the numbers behind the charts: foreginers have $6.6 trillion worth of RMB-denominated assets, roughly split 50/50 between direct investments and liquid assets. Never in the history of China this has happened before: prior to WWII, China issued securities but they were effectively issued in gold or sterling.

These are local currency assets: in other words, when you sell the assets you sell the currency. Flows are very difficult to forecast: but there is a vulnerability that hasn’t existed before because it wasn’t possible for anybody to liquidate over US$3 trillion worth of liquid assets because they simply didn’t own them. But given the great movement into liquid portfolio assets in china in the last 10 years, they are now there.

It all feeds into the monetary policy. Not shown in the chart below (the numbers just came out before the webinar), but in Q1 2024 growth in Chinese commercial bank assets was just 4.2%, off the bottom of the chart. This is the wellspring of money creation, even in a quasi-command economy such as China.

This country is heading for deflation unless it turns around. And you don’t turn it around while having your monetary policy influenced, never mind driven, by the condition of your external account and your exchange rate.

China needs easy money. The private sector debt service ratio is above 21%, an exceptionally high number, vs 15% for the US: historically, the dangerous level has been above 20% (again, not easy to divide between state and corporates, but that’s it).

However, unlike most other countries, China has falling interest rates and also a considerable degree of financial repression already in place. We thus need to look at China differently from other highly indebted countries. China is also very much a country that must and will inflate away its debts. It has yet to begin to do so. When it does it will be the resulting decline in the RMB exchange rate that changes the world.

China’s enemies now control its monetary policy, because they are increasingly controlloing its current account: as long as Xi chooses the exchange rate as his target, he is passing control over its monetary policy to those he believes are trying to contain it.

To break out, in Napier’s opinion, the RMB exchange rate has to be free floating. And it will fall, because China needs to at least double the rate of growth in broad money from 7% to 14% to try and get the debt-to-GDP ratio down (it has been going up when the growth rate in money was “only” 7% to 12%).

And if you double the expected growth rate in the supply of your currency, you might expect the exchange rate to decline.

China needs a monetary policy fit for its new reality and that reality is not just that it is now one of the world’s highest indebted countries. The other reality is that the country can no longer bet on exports to drive economic growth as the rest of the world’s move to contain China restricts such a growth path. The other reality is that the massive investment boom from 2009 to 2019 cannot be replicated given the scale of that malinvestment, the creation of excess housing stock and the inability to export the products of even further investment.

In a system with market determined interest rates there would be a jump in interest rates as there has been in the developed world post-2020 if such a form of reflation produces inflation. However in China, where the CCP controls the savings institutions, such a jump in interest rates could be muted. Xi could force savings institutions to buy government bonds and keep bond yields low, mitigating a negative to the domestic economy from this form of reflation. Xi likes control and he has all the control he needs to engineer a reflation of the Chinese economy while keeping interest rates low and thus inflating away China’s excessive debt burden. Xi has much more control than Ben Bernanke, and ‘Helicopter Ben’ managed it using the central bank balance sheet. Xi, in pursuit of ‘common prosperity’, is much more likely to use the commercial bank balance sheets to create his escape from the brewing debt deflation.

For those contemplating a punt on listed Chinese stocks as the beneficiaries of higher Chinese inflation, a word of caution. A reflation will push the price of Chinese equities up but it will also push the RMB exchange rate down, as imports boom and the current account worsens. This devaluation may be surpassed in magnitude by the rise in the price of Chinese equities. History suggests that it is a decent gamble to make, that a devaluation by a country not laden with foreign currency debt will lead to equities rising by more than the exchange rate is falling. China’s foreign currency debt is low and thus Chinese equities would probably produce positive returns even in foreign currencies on such a reflation.

Charles Gave: China is managing the currency for entire Asia

According to Charles Gave, China is not interested in having a reserve currency: they do not care at all!

Monetary system used to be like a big mainframe computer with the dollar at the centre of it: if France wanted to buy something in the UK it first had to get the dollars to pay the UK. Everything had to go through the dollar and you needed dollar reserves because they were needed mostly to buy energy.

That world is now gone: the mainframe is going to be replaced by a multitude of PCs. For example, India has a direct payment link with Singapore: they can trade in their own currencies, they don’t need to go through the dollar even for oil.

Financial reserves become useless, we don’t need all those dollars that are floating around: all the money that has been accumulated over decades will flow back to the US and create massive inflation there.

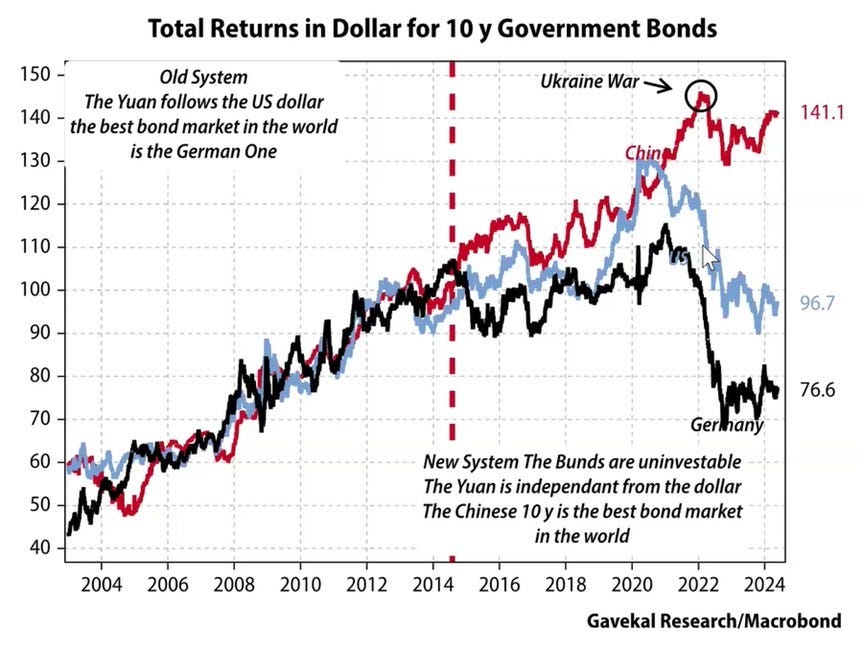

More important: China is not managing its currency for its own economy, rather for the entire Asian bloc. Here is a chart of the total return on 10-year government bonds over the last two decades: there was a massive change in the last 3-4 years and now the Chinese bond market is independent from the US.

From 2004 to (more or less) the EU crisis, all the “good” bond markets were driven by the USD: there was no choice but to follow the US. But China has broken out of it when the US and German bond markets started crashing, to the point that the volatility of the Chinese bond market – measured in USD - is way better than for US treasuries.

From the Asian point of view, as far as investments are concerned the US is full of risks, while China is the risk-free asset and China (not the US) is now determining the cost of capital for all Asian markets. So, if you want to build foreign reserves you should do it with Chinese bonds!

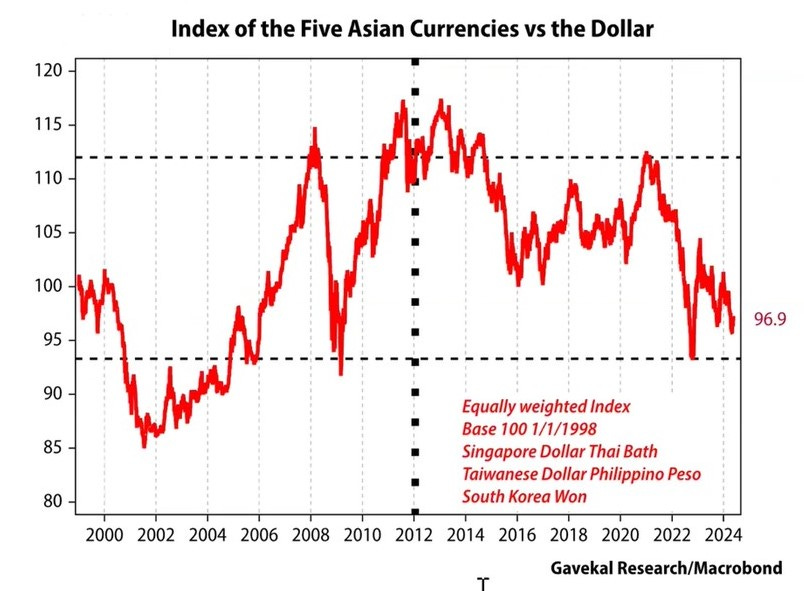

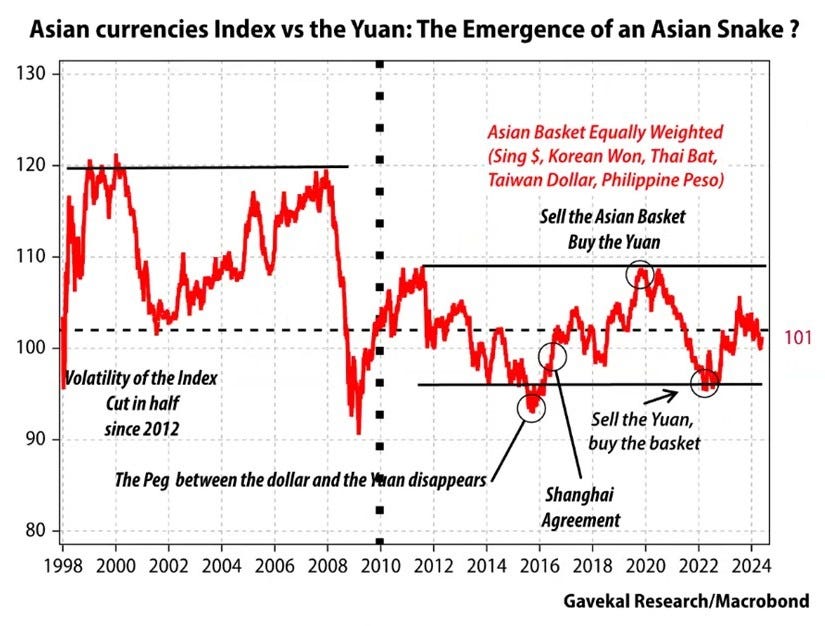

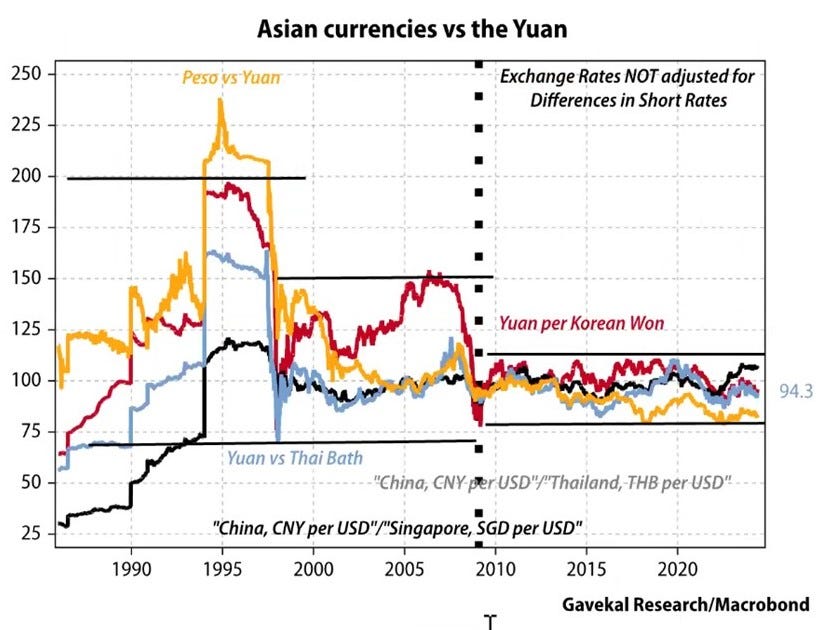

Take for example an equally-weighted index of 5 currencies (SGD, TBH, PHP, TWD, KRW) vs USD: it shows a lot of volatility over time.

Now take the same basket vs RMB: much less volatility, especially since the aftermath of the GFC. There is clearly an attempt by these five countries to manage their currencies vs RMB.

A totally different world from what we were used to. China’s “unspoken” proposal is: “You stabilise your currency vs mine, and I will stabilise the basket vs the rest of the world”. Not a full-scale exchange-rate mechanism, just an agreement. If you take individual currencies, the emergence of a monetary zone in Asia is evident.

So China’s goal is not to manage the currency for its own country but to become the long-term provider of capital to the region. Most of China’s trade is indeed going to these countries, and you don’t need foreign reserves to do it: expect massive growth in government debt from these countries to settle trades with each other.

Louis-Vincent Gave: RMB will revaluate

We have been told for the last 12-15 years that the RMB was going to devalue: the reality is that it’s one of the most stable currencies out there.

Over the last three years China has experienced a big bear market: shares have gone down two thirds, real estate prices down by one third – a debacle for investors.

Yet, nobody has made it out like a bandit on this implosion: bond markets haven’t collapsed, and the currency has been stable. The system kept it together: no bank failures, no government bond implosion, no massive devaluation as it typically happens in an emerging market crisis.

Every HF over the last 10 years had got the China call wrong. And if you still think that a currency implosion is right in front of us, you might be again very wrong. Just look at the rebound in Chinese equity markets over the last few months and metals prices at all-time highs.

Look at recent news: Xi has been berated in Europe (Chinese spies have been arrested in Germany, von der Leyen complained about overcapacity); US imposed tariffs on Chinese goods and tries to ban TikTok; Xi publicly hugs Putin while openly displaying tensions during recent visits by Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Secretary of State Antony Blinken. Few months ago this would have led to massive capital outflows from China and sent the equity markets crashing down: it did not happen this time.

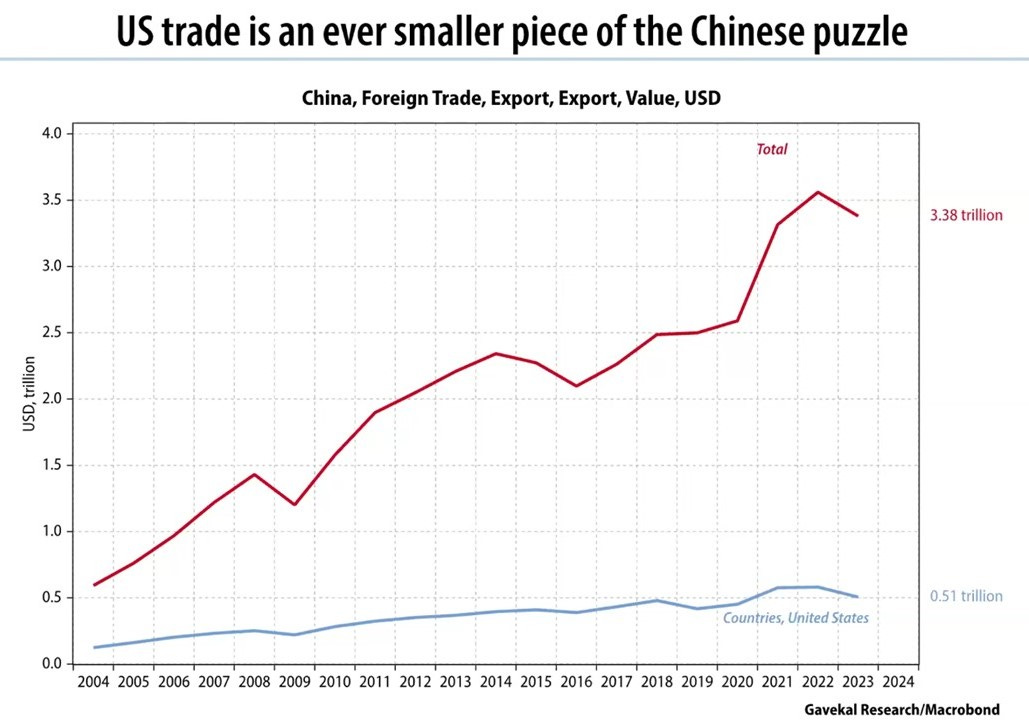

China’s trade with the US has flatlined since 2020 (Mexico is now the US biggest trade partner), but not with the rest of the world: China’s exports to the “Belt & Road” countries are now bigger than exports to US and Europe combined. It’s true that part of it is just repackaged (goods are sent to Vietnam, get a “Made in Vietnam” tag and are then shipped to the US), but a lot of cars/tractors/etc sold to Indonesia, Vietnam and other countries remain there.

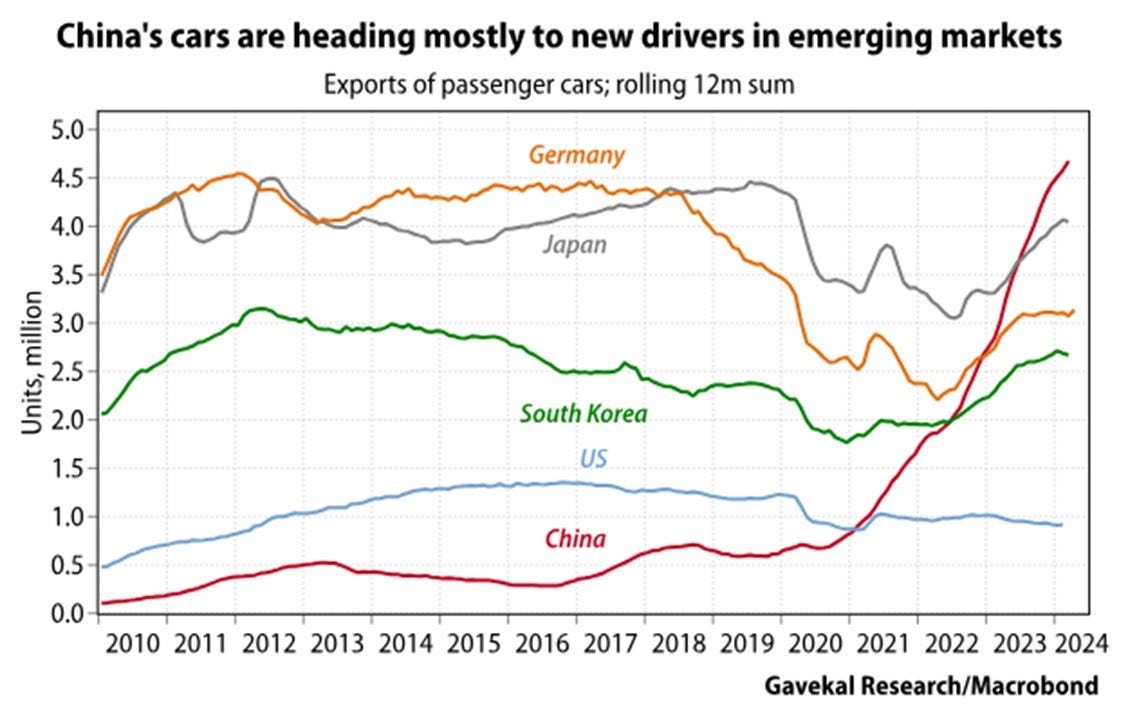

China’s trade is actually going gangbuster: from nowhere 5 years ago now China is the world biggest car exporter (same is valid for tractors, earth moving and railroad equipment, telecom switches, solar panels, …). And this despite a backdrop of decently stable RMB. Suddenly, the rest of the world is worrying that China is set to become even more of a deflationary drag on global growth than it has ever been, as it moves to export this new overcapacity.

Today the US is all about “re-industrialising” (bring back auto jobs to Michigan, …), and you can’t do that with an overvalued currency: the US administration is telegraphing that it wants a weaker USD.

Look at the 1985 Plaza Accord: what were the best performing markets? Hong Kong and commodities. Same thing has happened over the past 3 months.

(Also see his piece: The China Quandaries)

Q&A

Russell Napier (RN): I agree on China’s reflation and stocks will go up: the market is currently on a cyclically-adjusted PE of 10x, traditionally a good time to buy.

But reflation can only happen if they abandon the managed exchange rate. How do you reflate your economy? Not rocket science: get banks to lend money (via central banks or commercial banks), that creates higher nominal GDP but put pressure on the exchange rate to fall.

Charles Gave (CG): there is a big difference. China has a huge amount of debt balanced with massive amounts of assets (highways, nuclear plants, barracks, which could be sold to the public if needed – at least in theory, ndr). Europe and US have huge amounts debt and no assets on the other side.

It’s just generational: debt in your own country is to yourself (that’s why he says that Japan never had any debt, and China also does not have a debt problem).

RN: China has a high corporate debt-to-GDP, the highest in the world, and also a high debt service ratio for private debt. Government debt/assets are not a big deal: the issue is in the private sector.

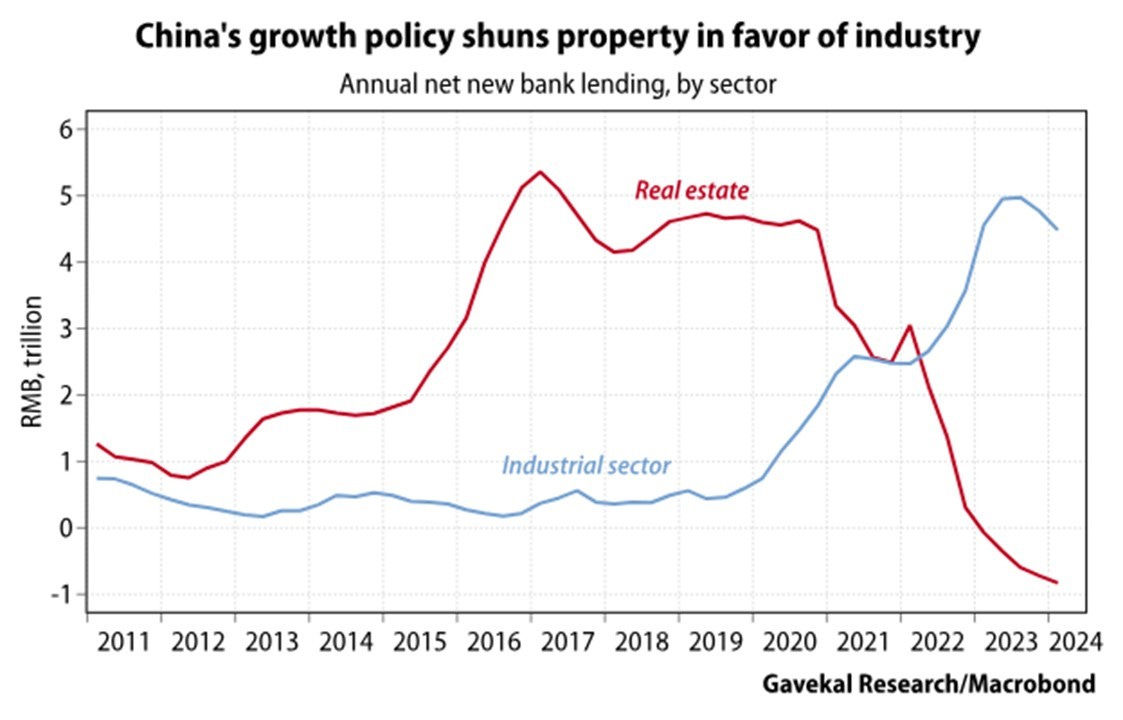

Louis-Vincent Gave (LVG): if debt goes into productive assets, it’s ok. With the US banning semiconductor exports, China was forced to invest heavily in order to move up the industrial value chain (see the massive improvements in industrial efficiency). In an age of great power conflict, China had to quickly cut its reliance on the broader Western world. Banks were thus “encouraged” to forego lending to real estate developers, and instead focus their loans on building up China’s industrial backbone, as shown in the chart below.

RN: but the private debt sector service ratio keeps going up, not down, despite interest rates moving down. So maybe they are not getting returns high enough in the industrial sector commensurate with debt (malinvestment), as it happened in real estate?

LVG: if there was a real debt problem, with everything that we witnessed over the last 3 years, you would have seen banks collapse: it did not happen.

RN: these are state-owned banks, in developed countries there are private banks: the government will not allow state banks to go bust. Quite the opposite, banks are going to increase lending, which puts pressure on fx.

Also, nice currency charts guys, but most Asian countries have come out against China recently. Japan in particular, it fears it might happen something worse than Ukraine. South Korea and Taiwan are obviously with the US, the Philippines also on its military side, and Vietnam buys armaments from US.

This Asian currency bloc depends very much on the US for their own defense: can China bring them in a currency bloc when they are in a military bloc with the US?

CG: diplomats lie, I don’t believe what countries say, I believe in what they do, and they do stabilise their currency to RMB, not USD.

A debt deflation is when falling asset prices spur debtors to repay their debts, which can lead to an aggregate contraction in bank credit that will reduce the money supply, which likely produces a further fall in asset prices. There is thus a very negative feedback loop which sees further loan repayments, further contractions in liquidity and further falls in asset prices. The best-known example of a debt deflation occurred during the Great Depression.

This form of reflation did not promote ‘common prosperity’ when used in the US: rather, it exacerbated inequality.