Intermediate Capital Group

Under the radar but fast-growing player in an attractive industry

Fourth post on listed alternative managers, after VNV Global (venture capital), Petershill Partners (GP solutions) and Blackstone Loan Financing (CLOs).1

Intermediate Capital Group ($ICP.L) is a UK-based global alternative asset management company offering a range of strategies across private equity, private debt, real assets and credit strategies.2

Despite its long history, AUMs (US$82 billion) and current market cap (US$5 billion), ICP is very much unknown: I doubt many fund managers outside of London are familiar with the company.

There is no controlling shareholder, all the shares are free float and the largest holder is Aviva Investors at less than 6%.

History

ICP was founded in 1989 on the principles of flexible capital solutions, with a focus on investing its own capital in an emerging asset class for mid-market European companies: mezzanine debt, a layer of debt refinancing between equity and fixed income.

In 1994 ICP listed on the London Stock Exchange and began managing funds on behalf of other investors; in 1995 it opened an office in Paris and in 1998 it raised €50m for their first European fund. Assets under managements reached the milestone €1bn in 2000, the year it issued Europe’s first CLO fund (Eurocredit 1, at €450m). In 2001, the Asia Pacific office in Hong Kong was opened, followed by Madrid (2003), Frankfurt (2004), Sydney (2006) and New York (2007): today, ICP has 16 global offices.

In 2008, like countless other financials around the world, with an illiquid portfolio of private debt investments it faced enormous challenges in weathering the impact of the global financial crisis. To help support clients, it launched the Recovery Fund 2008, leveraging opportunities in the loan market and providing much-needed relief for businesses.

The crisis became the catalyst igniting the diversification strategy across asset classes and geographies, developing a third-party investment business and building a dedicated client function. In 2012 it launched its inaugural direct lending strategy, filling the hole left by the retreat of traditional lenders. That year also laid the foundation for the real assets business with ICP taking a 51% stake in Longbow, a UK real estate financing business (fully acquired in 2014).

In 2015 it also took over Graphite Capital Management's private equity fund-of-funds business, inheriting the management of the Graphite Enterprise Trust, later renamed ICG Enterprise Trust and today a FTSE250 company in its own right.

Asset classes

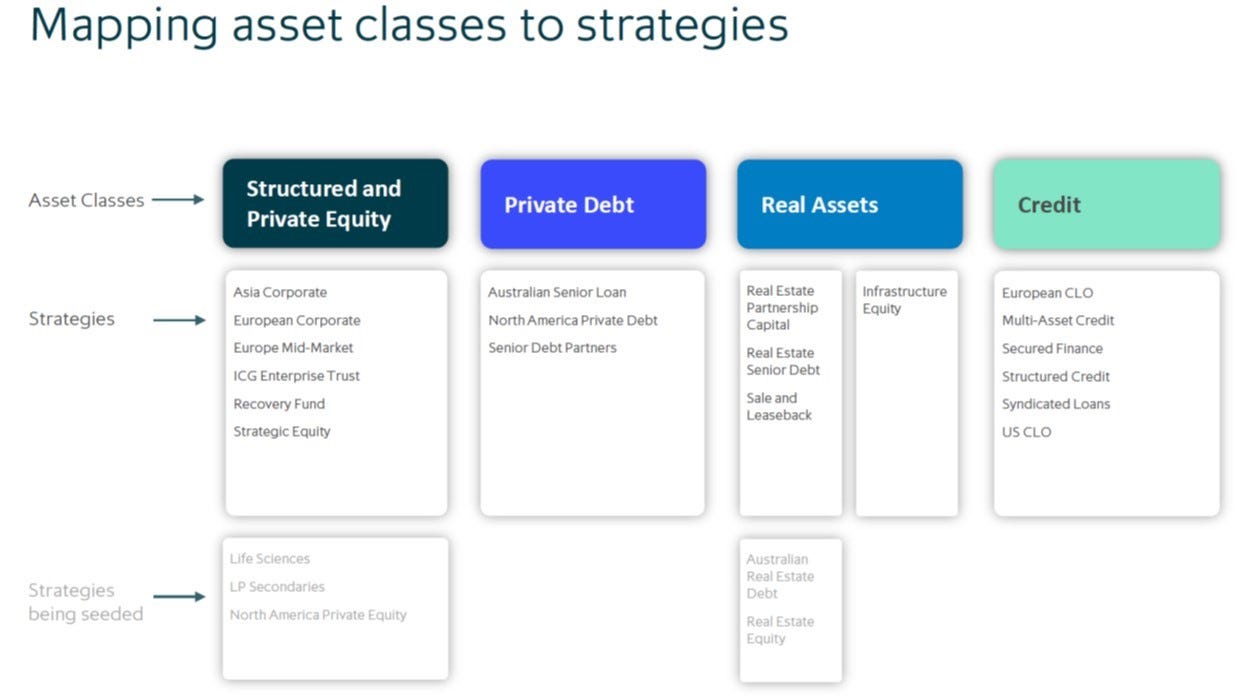

ICP investments are spread over four macro-strategies:

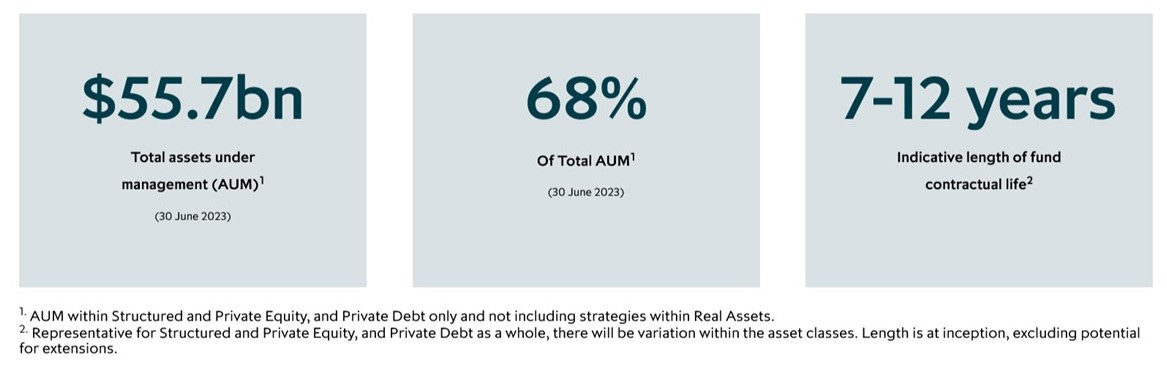

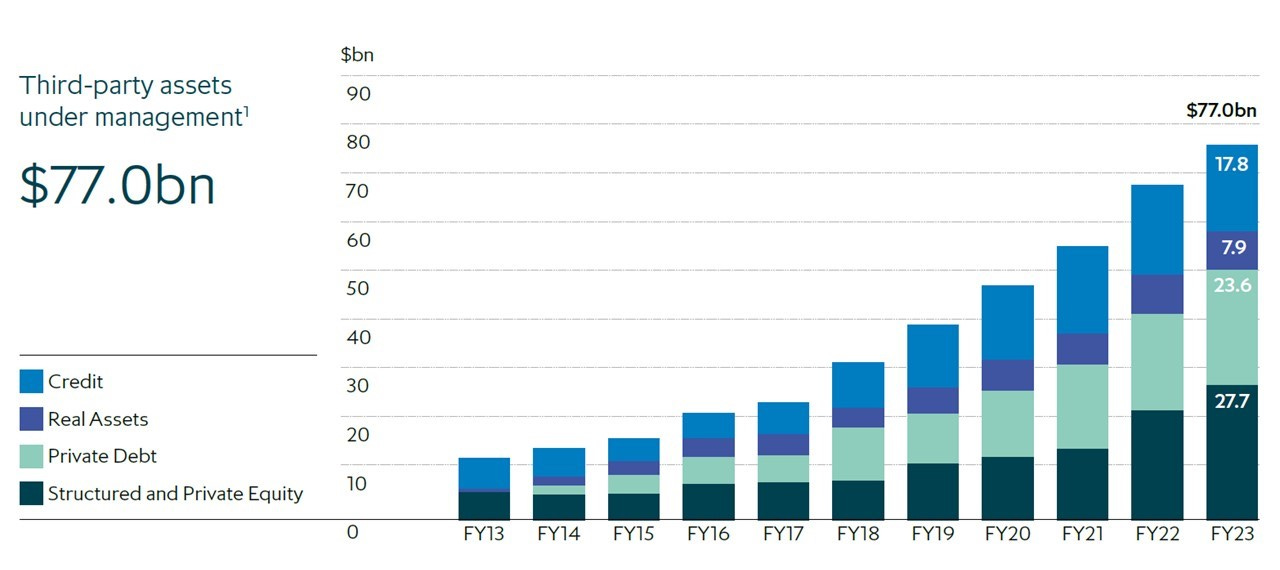

1. Corporate strategies (include both private debt - $23.6 bn – and structured/private equity - $27.7 bn)

European Corporate & European Mid-market: ICP’s flagship strategies with a 33-year track record, target locally sourced, directly originated and privately negotiated investments in European corporates (high quality mid-market and upper mid-market private companies with enterprise values between €100 million and €2 billion), supporting family owners, founders and management teams in realising their objectives for long-term, sustainable value creation

Recovery Fund: to invest in undervalued assets in dislocated markets, currently focused on the post COVID-19 pandemic. As a tactical platform, the Recovery Fund also co-invests alongside other ICP strategies across the capital structure, asset classes, industries and jurisdictions

North American Private Debt: private debt solutions for both private equity-sponsored and independent corporate borrowers, typically for businesses with EBITDA ranging from $25 million to $250 million. Investment sizes range from $50 million to $1 billion across a range of debt securities including senior secured debt, unitranche debt, second lien debt and subordinated notes

US Mid-Market: targets sectors where the team can leverage its experience and thematic focus (sector preferences: business services, consumer, healthcare, industrials), with a strong preference for founder and family-owned businesses

Asia Pacific Corporate: the Asian version of the European flagship fund with an 18-year track record, it targets locally sourced, directly originated and privately negotiated flexible subordinated debt and equity investments in Asia Pacific middle market companies

Australian Senior Loans: a diversified portfolio of senior secured loans to established companies

Strategic Equity: focused exclusively on the GP-led secondaries market, since its launch in 2014 it has committed over US$12 billion into some of the largest and most complex continuation vehicles globally

LP Secondaries: 100% focused on limited partnership (LP) liquidity solutions on a global basis

Life Sciences: focused on creating and building life science companies addressing commercially attractive markets in diseases of high unmet medical needs

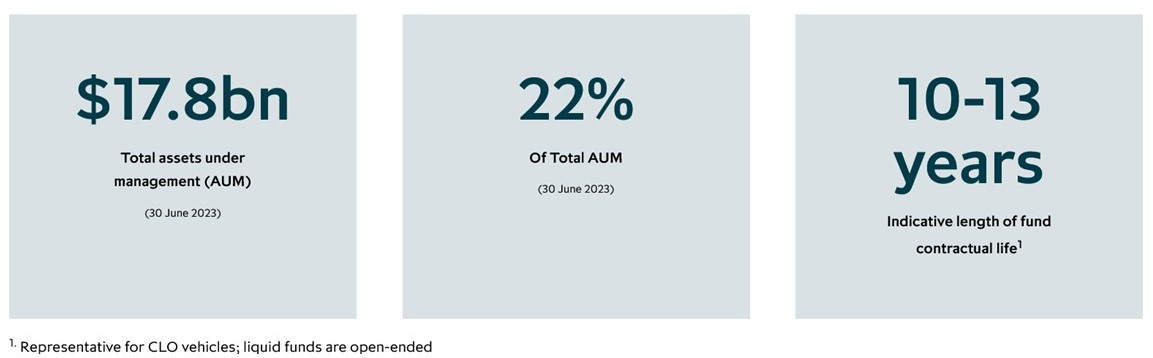

2. Credit

Liquid Loans: senior secured floating rate loans, a high conviction portfolio of 100 to 125 “best ideas”

Multi-Asset Credit: senior secured loans, high yield bonds, collateralised loan obligation (CLO) debt, and special situations investments in the US and Europe. Again, a portfolio of 100-125 “best ideas”, based on a broad opportunity set and flexible parameters permitting dynamic asset allocation and disciplined issuer selection

Alternative Credit: focus on credit dislocations, it seeks to capture excess return through identifying price inefficiencies in structured assets and acquiring credit portfolios from financial institutions. It also provides replacement capital for investment activities previously undertaken by banks.

3. Real Assets invest in real estate assets (including infrastructure) and platforms internationally, across the capital structure in both equity and debt.

How it’s going

Today, ICP is two (closely related) companies within one corporate structure:

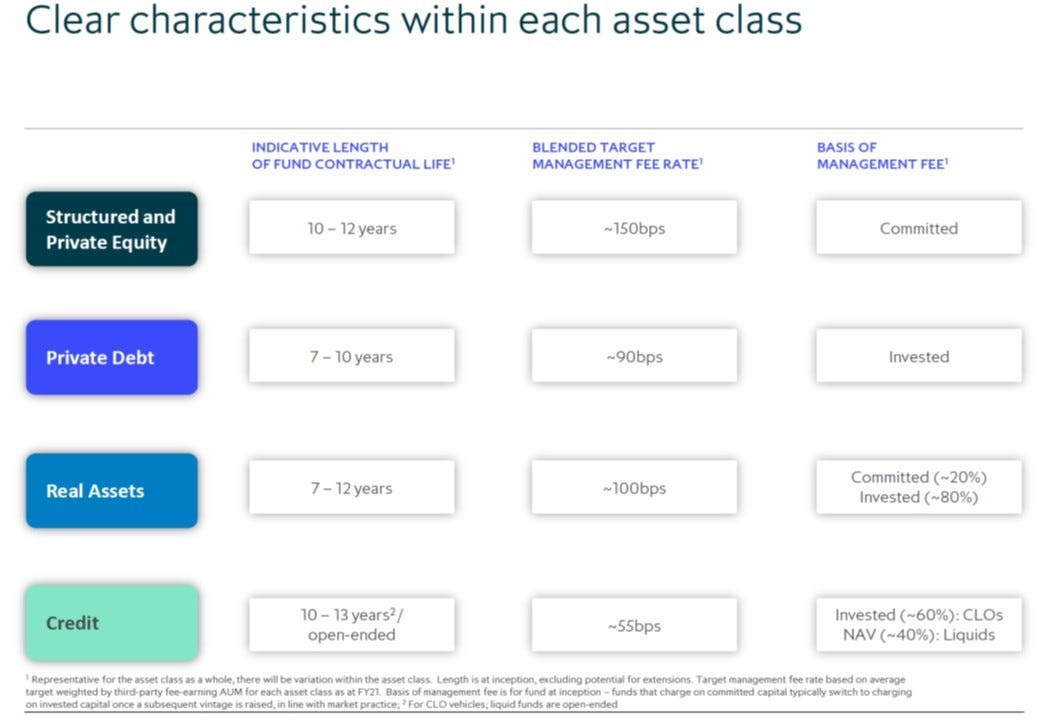

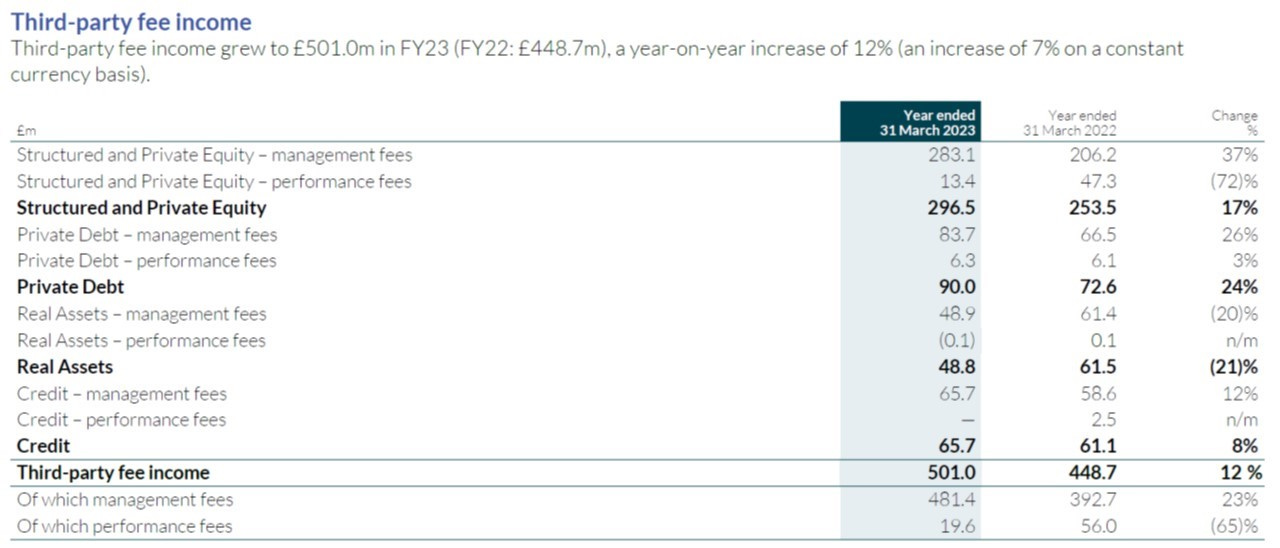

A Fund Management Company (FMC): the group’s principal driver of long-term profit growth, it manages the third-party AUMs on behalf of ICP’s clients. Revenues are primarily generated from management fees (a blended average of ~90 bps across products), with additional contribution coming from performance fees (which typically average ~10-15 bps) and dividends received from the equity slices of the CLOs they manage

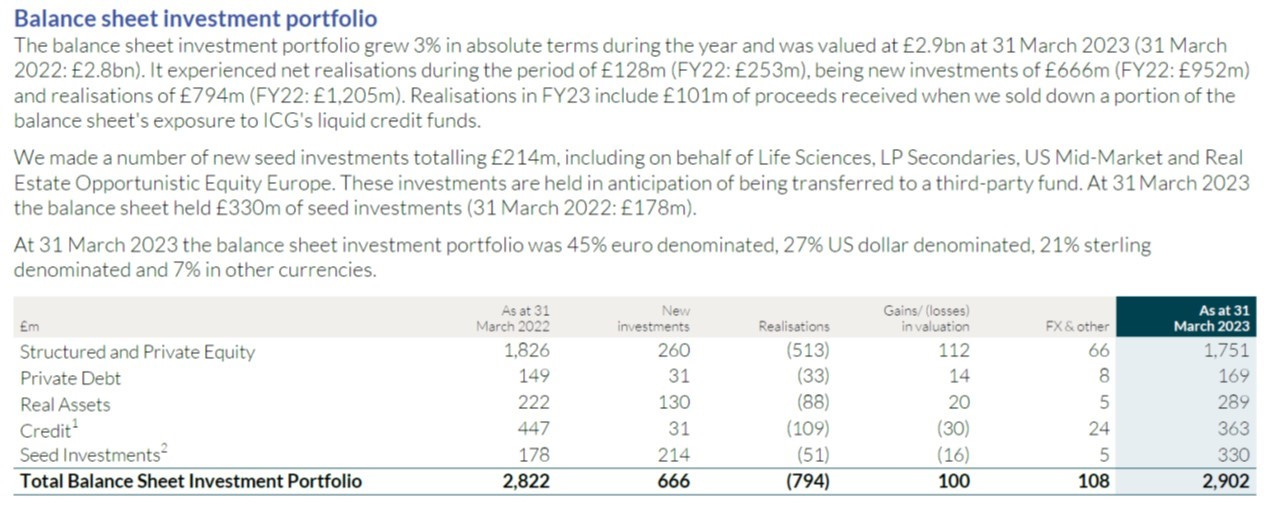

An Investment Company (IC) which invests the group’s proprietary capital (called “balance sheet investment portfolio”, currently around £3 billion) to seed and accelerate emerging strategies. Revenues are generated from interest income, dividends, and gains and losses on the direct investment in their own funds.

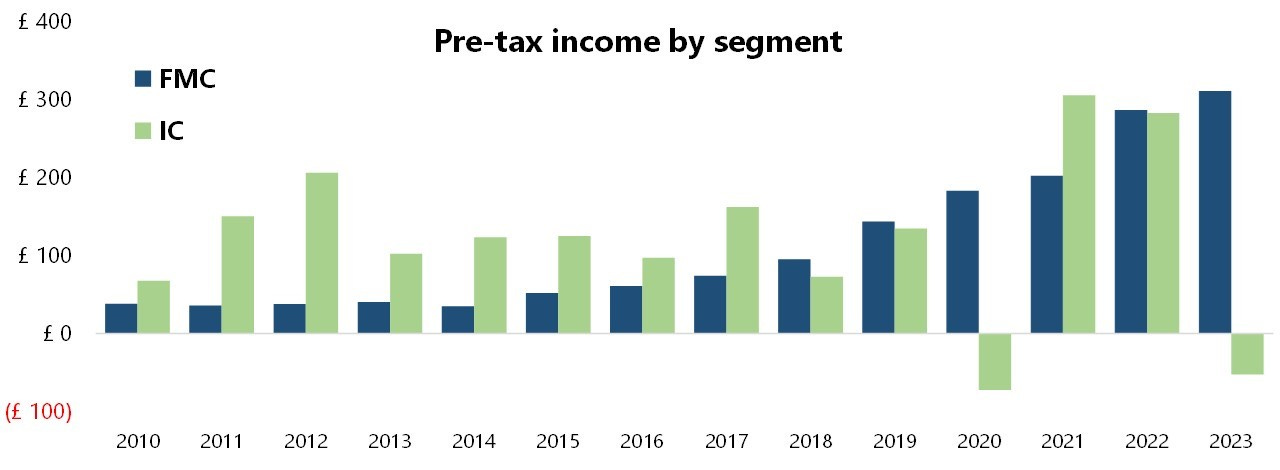

While only few years ago pre-tax profits were 70%-80% from IC, today the situation is more evenly split (depending on the underlying performance of the funds): revenues and profits from management fees are way more stable and predictable, and their contribution should increase further over time.3

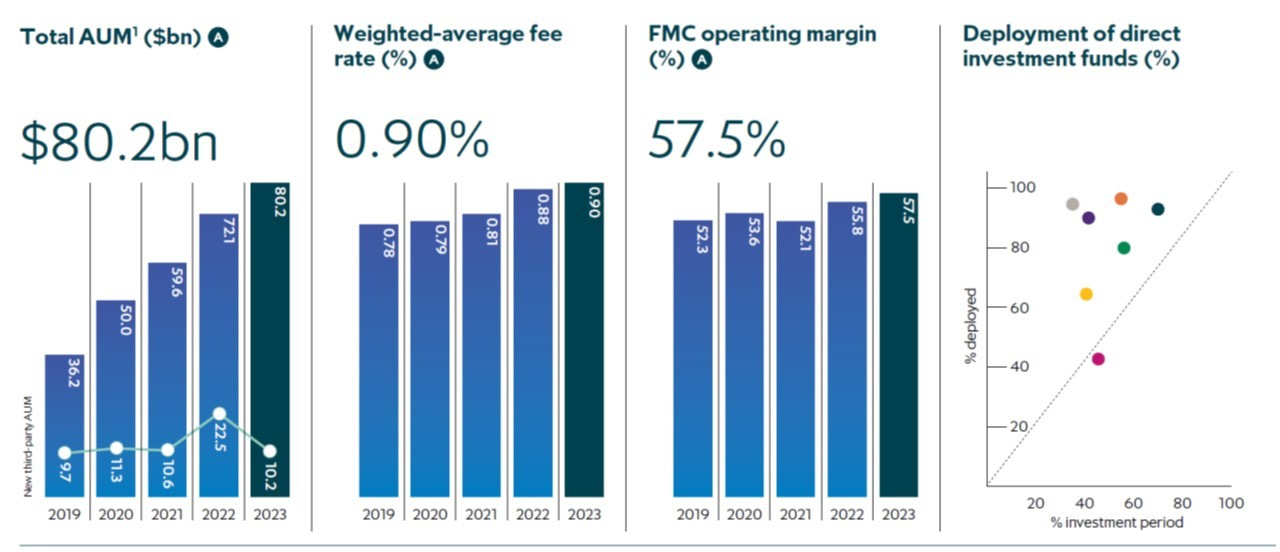

Despite keeping the balance sheet investments at around £2bn - £3bn, AUMs have really started to ramp up since the corporate strategy was refocused towards more third-party investments: at 30 June 2023 the total is now US$82.1 billion (including its own invested capital). Over the last decade ICP raised roughly US$100 billion in aggregate from clients and this has been the result of increasing the size of existing strategies (“growing up”).

In FY2023, US$10.2 bn of new money was raised, of which:

US$3.5 bn in Structured and Private Equity

US$3.8 bn in Private Debt

US$1.1 bn in Real Assets, including a second fund dedicated to Sale and Leaseback

US$1.9 bn in Credit

Notwithstanding a slowdown in transaction activity across the markets, US$5.3 billion fee-earning AUMs were realised from the direct investment funds (FY22: US$6.4 bn).

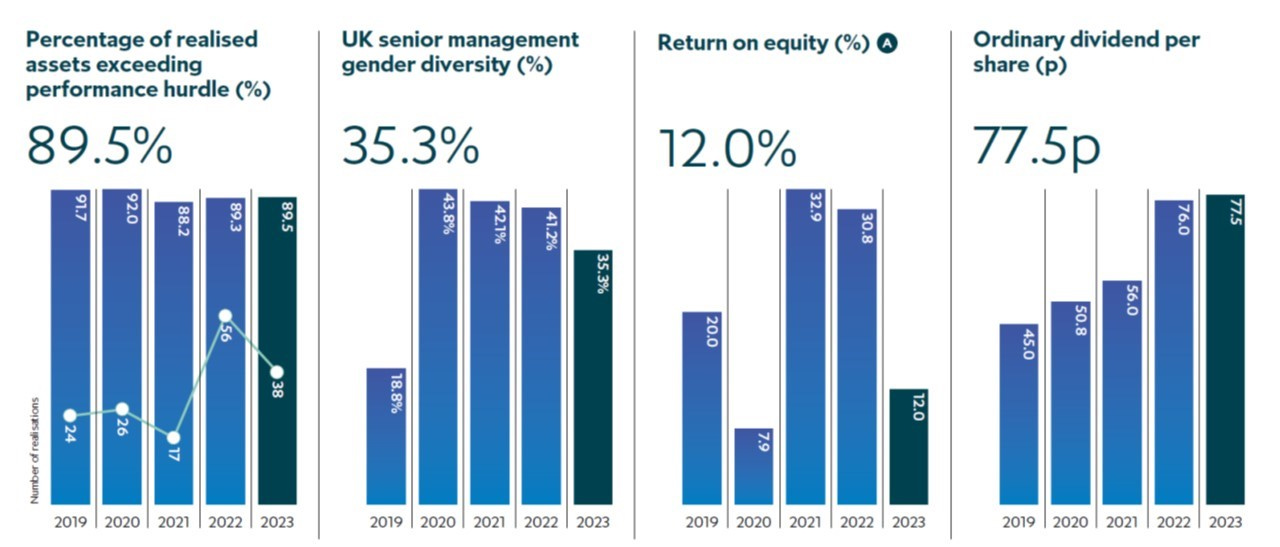

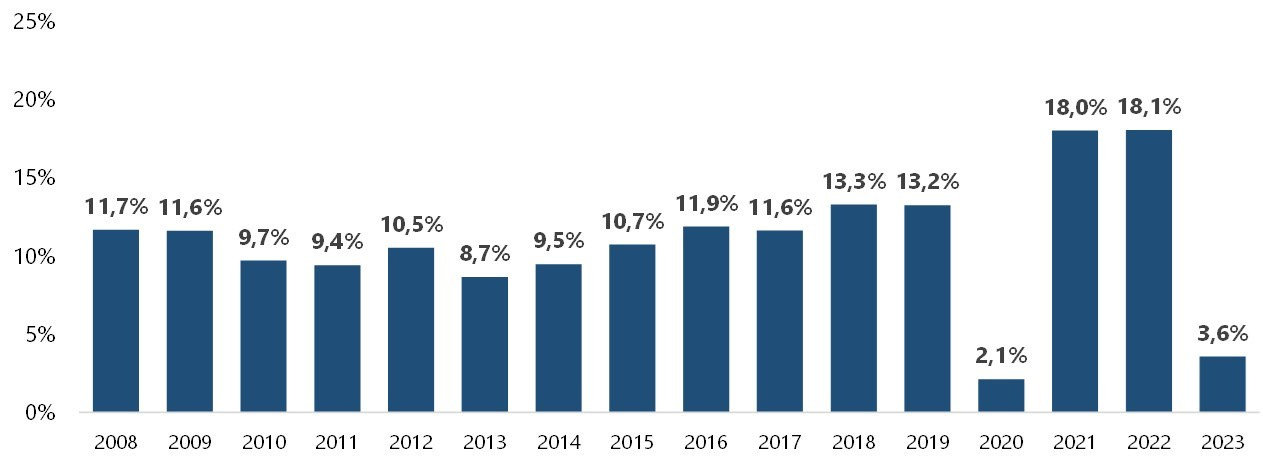

What has allowed the growth in third-party AUM has obviously been the good aggregate performance track record, with ~90% of realised assets exceeding their performance hurdle rate: as a proxy for LPs’ performance, ICP’s return on its own investments in its funds has been ~11% annually since 2008, with no down years.

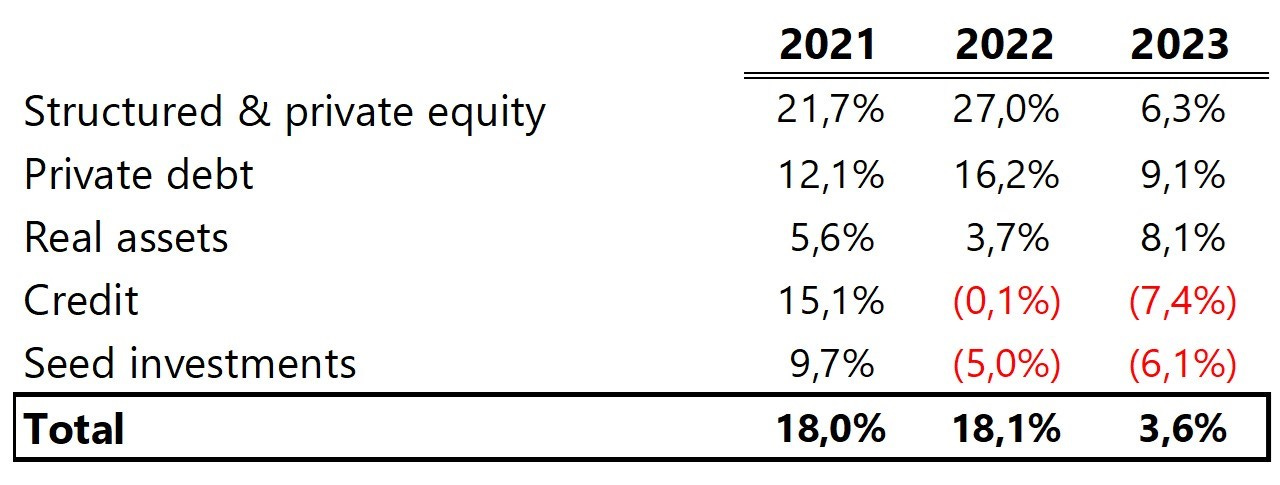

Not surprisingly, 2020 (Covid) and 2022-2023 (interest rates hikes) have been the worst performing periods, mostly for the impact of credit strategies. A detailed performance by asset classes for its own investments has only been available for the last three years, here is how they performed.

Growth strategy

ICP hasn’t had a full Investor Day since pre-Covid, but last January they held a “Fundraising and Client Strategy Shareholder Seminar” to update analysts on their future strategy.

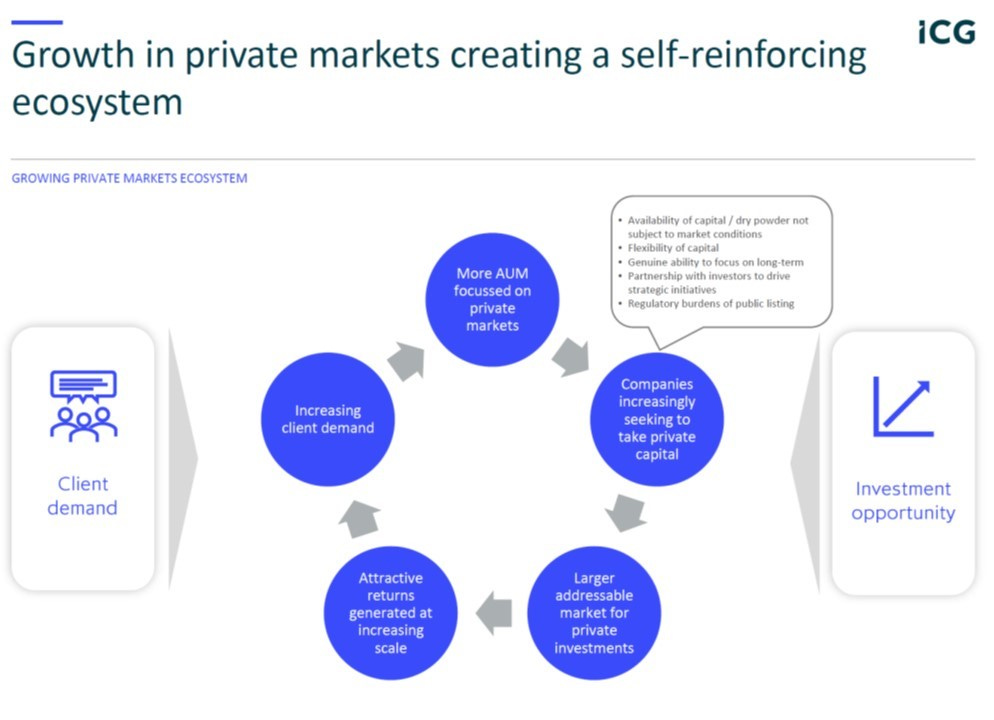

Private markets have become more and more accepted by assets owners and are increasingly seen as a “mainstream” asset class (not just “alternative”), with sub-asset classes at different stages of maturity (for a detailed discussion see the Peterhill’s post): ICP’s AUMs are up 6x over the last decade vs. a 4x increase for the broad market.

What explains the increasing demand? It wasn’t just a search for yield in a low-rate environment. Attributes such as high returns, partly a function of illiquidity or complexity premium, and access to asset classes with inflation-linked protection are key attractions to private market strategies and differentiators versus public markets, as is the ability to match long-term liabilities with long-term assets – particularly compelling to investors with long time horizons: for insurance companies, this duration matching is a real driver.

Regarding the last point in the slide above (access to companies in different parts of the economy):

“[…] if you’re a mid-size business services, education, or healthcare business in the western world today, you probably have no need to ever raise public capital in the debt or equity markets. You may choose to do so for a variety of reasons, but you do not need to, as the private markets are sufficiently scaled and mature, that you can grow and monetize your business exclusively within private markets. As a client, therefore, investing in private markets gives you exposure to many parts of the economy that are increasingly difficult to access in the public markets. For example, high-growth companies, particularly in Europe, business technology and healthcare services, and of course infrastructure. In all, the reasons for clients investing in private markets are of course multifaceted and vary between client types, but they're based on long-term and strategic approaches, which are not really driven by a short-term tactical response to prevailing conditions at any particular moment in time. Finally, given the illiquidity and private nature of our business, dispersion and performance between manager and the arena is huge, so manager selection really matters.” (ICP seminar, January 2023)

At the same time, LPs are consolidating their GP relationships, giving more and more dry power to the largest asset managers. AUMs for alternative asset managers tends to be sticky, due to fund structures which lock up AUM for years at a time as well as the fact that “brand name” matters a lot more than it does for more traditional asset managers. LPs are most comfortable investing with established managers: this is evidenced by minimal fee rate pressure over time (a stark contrast to the rest of the industry).

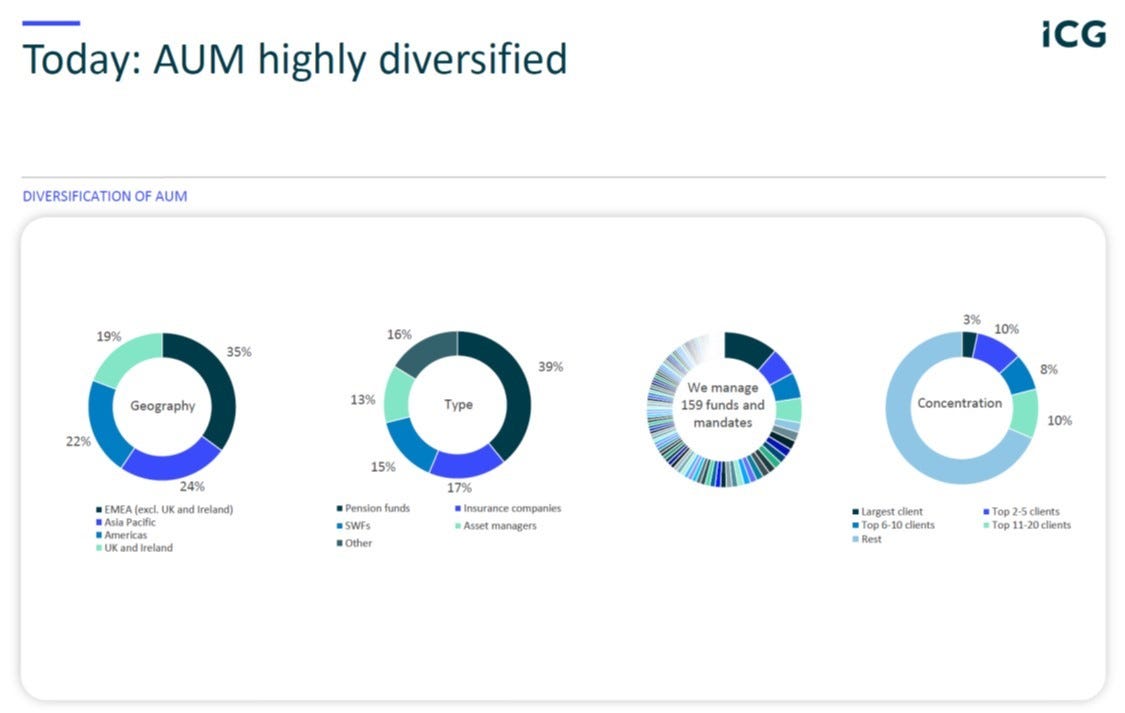

Today, ICP has over 600 different clients (up from 69 when the business model was reshaped), highly diversified by type and geography: clients have particularly grown in North America, including six of the top 10 allocators in the region. This growth in client numbers has also had the added benefit of reducing concentration: the single largest client in 2012 accounted for 16% of third-party AUM, while today this number is around 3%.

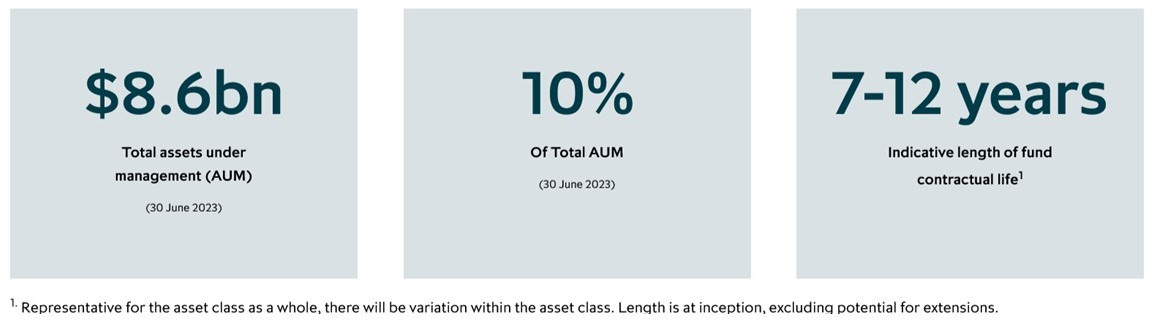

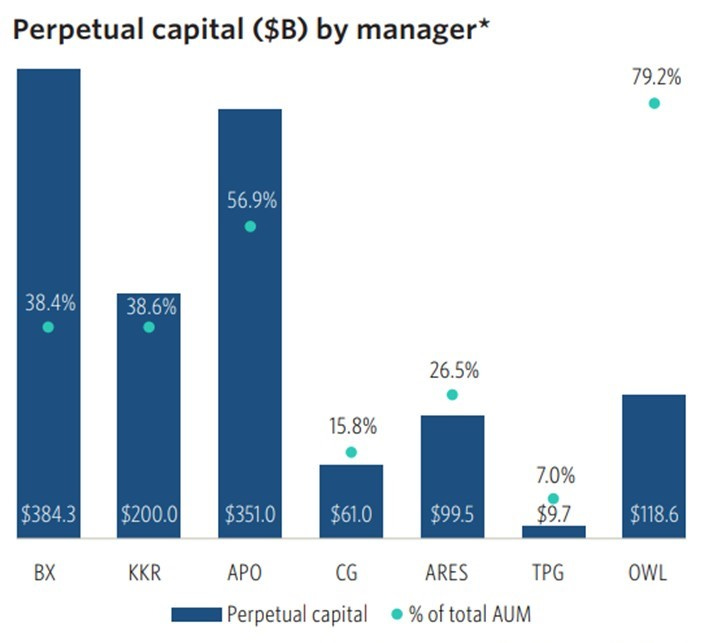

One minor point to note: while ICP’s funds have a long indicative length (~10 years on average), it has LESS perpetual capital compared to the biggest US alternative asset managers (for example, it doesn’t own a captive insurance company). ICP can only count on around £1 billion in ICG Enterprise Trust plus £100 million in another smaller trust (ICG Longbow Senior Debt) in addition to its own invested capital. Permanent capital is thus around 6% of AUMs, compared to around 40% at Blackstone and KKR and almost 60% at Apollo.

Recent trends: What other asset managers are saying

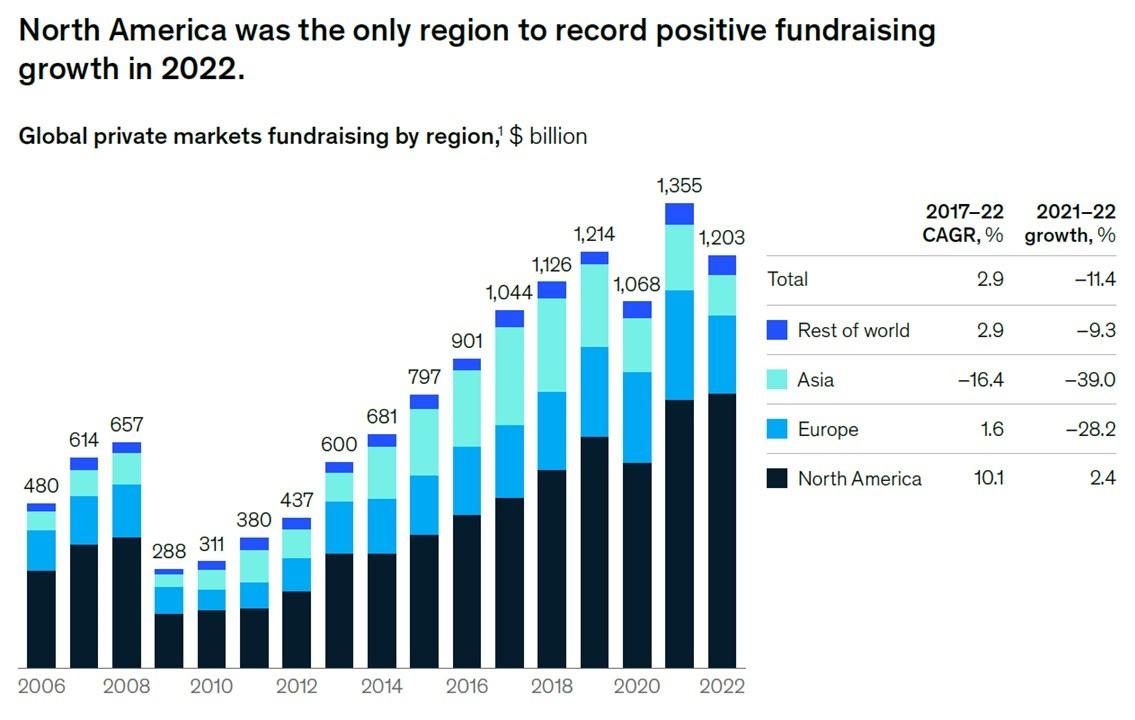

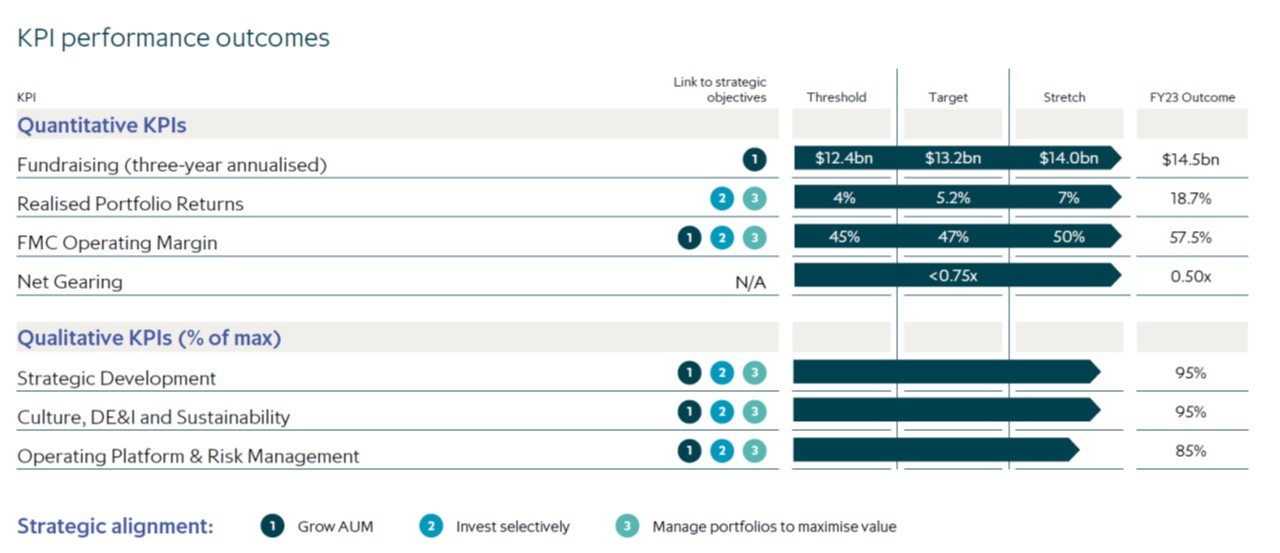

The last 12 months have signalled a softer fundraising environment: it was indeed the lowest fundraising year in Europe since 2015, with private equity down 37% year-on-year according to Preqin/Evercore. This was due to a combination of LPs’ risk-off considerations in light of macro-economic and geo-political uncertainties, and a high saturation of funds competing for capital. On average, ICP raised US$14.5 billion over the last three years (well above the US$12.5bn for management’s bonuses), but “only” US$10bn last year.

McKinsey has just released their annual Global Private Markets Review (free, but need registration), highlighting some of same issues:

“The music didn’t stop, but someone turned it way down. Private markets have enjoyed strong tailwinds since the depths of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Interest rates stayed low, credit availability was high, and valuations rose consistently. Each year since its inception, this annual publication has discussed new records in fundraising and deal flow while celebrating strong performance across asset classes. Even in 2020, when activity stalled briefly during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, private markets hummed again in the second half.”

“The mood changed in early summer (2022). Banks began to pull back, unwilling or unable to lend. Private markets deal volume plummeted, performance declined, and valuations fell - sharply in certain sectors. Still, private markets outperformed public markets on the way down, whether due to truly more resilient portfolios, a lag in timing, or manager discretion over their marks (private markets tend to mark up less quickly during ascending markets and mark down less quickly in falling markets).”

“The denominator effect took hold. Global private markets fundraising declined by 11% to $1.2 trillion. Real estate (−23%) and private equity (−15%) declined most precipitously from 2021’s record highs, while private credit (+2%) proved more resilient. Macroeconomic headwinds, including rising inflation and interest rates, coupled with sharply negative public market.”

Similarly, recent analyst calls with both traditional and alternative asset managers confirmed these two trends:

The fundraising environment is getting harder, especially for new equity funds; most institutional investors have reached their allocation limits in equity, while those that are allocating are preferring larger funds and managers, as well as credit and infrastructure strategies.

There continue to be significant opportunities in fixed income, driven by banks facing liquidity and capital issues, as well as the rise in interest rates; the shift to private lenders is expected to continue, given these fundamentals.

“It’s a complicated complex market environment. M&A volumes are about half of what they were just last year. IPO activity is sluggish. US leveraged loans are much smaller, smaller than they have been in many, many years.” (Curtis L. Buser, CFO, The Carlyle Group)

“We set our original flagship fundraising targets under different market conditions. We still expect each fund to grow compared to its predecessor. But in aggregate, they may not grow as much as we previously expected. We’ve already been managing the business with this in mind.” (Jack Weingart, CFO, TPG)

“The benefits from the use of leverage in the current environment is neutral at best negative in many cases. A different paradigm is required to invest successfully going forward, one that focuses on the investment merits of selected asset classes and creating alpha at the asset level to drive return premiums for equity investing.” (Robert Morse, Chairman, Blackstone)

“The most interesting opportunities currently in the pipeline are in the debt markets, where we can step into the funding gap for refinancing opportunities and provide fresh capital on a structured basis.” (Michael Arougheti, CEO, Ares Management Corporation)

“In credit, higher base rates, wider excess spreads and greater investor protections have led to an attractive and building investment pipeline. Said simply, it's a great time to be an opportunistic credit investor.” (James S. Levin, CEO/CIO, Sculptor Capital Management)

Management remuneration

Last year, ICP’S Remuneration Committee consulted with shareholders on a proposal to reposition the CEO/CIO base salary, currently at £410k (quite low compared to what CEOs are paid at similar asset managers: the new CFO, recently hired, was indeed given a base salary that is almost 50% higher than the CEO) to what they call a more typical “benchmark level” (£760k-£800k). The Committee decided to approve the salary increase, which will be repositioned in gradual increases over the next three years.

In terms of variable/performance pay, the CEO currently has a cap of 8x base salary (i.e., max £6m in FY2026), with at least 70% of this deferred into ICP shares vesting in 3 to 5 years.

Both the CEO and the Executive Directors have remuneration pay structures based on a simple, single performance scorecard, designed to emphasise sustainable, profitable growth and align their interests with shareholders (Executive Director’s performance bonuses are also mostly in the form of deferred shares).

Valuation

ICP’s “re-focusing on third-party AUMs” strategy has worked quite well, with the stock price up almost 12x since the trough in early 2009.

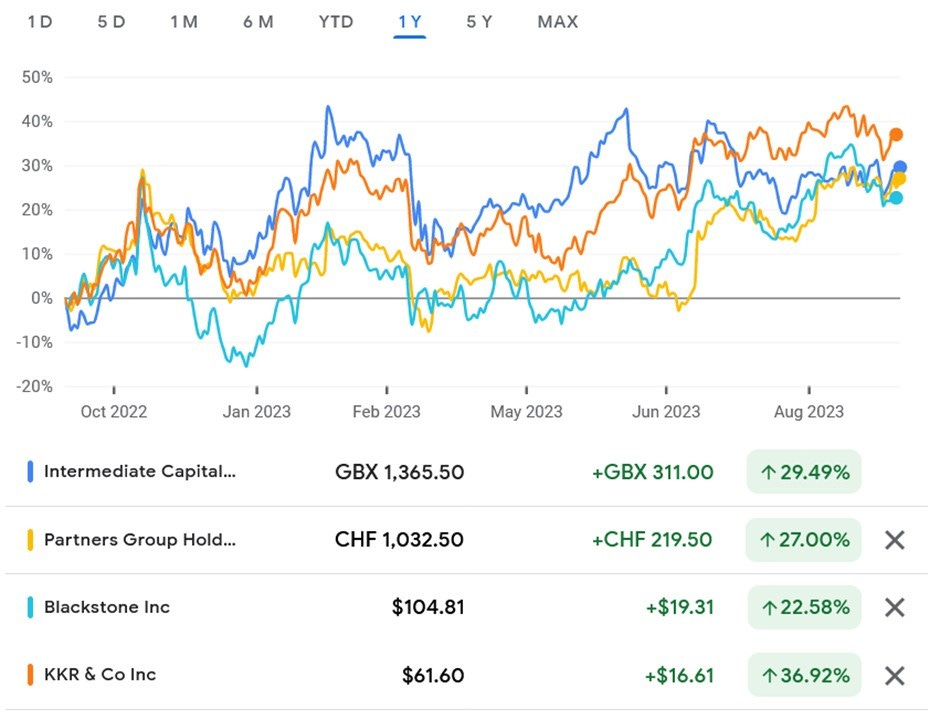

However, after touching a peak of ~£23.5 in late 2021, the price has now retraced by more than 40% to the current £13 to £15 range (but up +19% YTD): like many other alternative providers, ICP’s performance is quite sensitive to movements in interest rates. Performance over last year has not been too dissimilar from its largest and more famous peers.

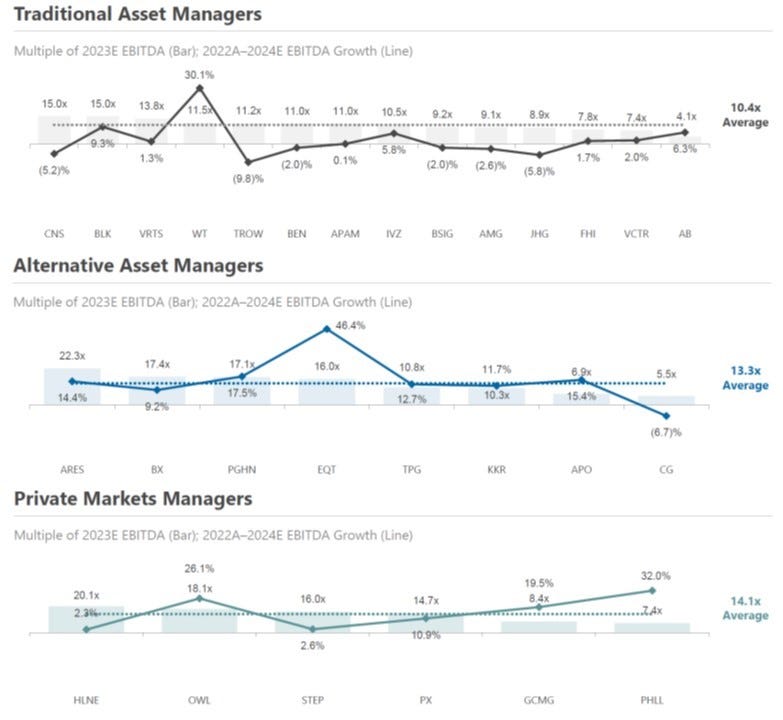

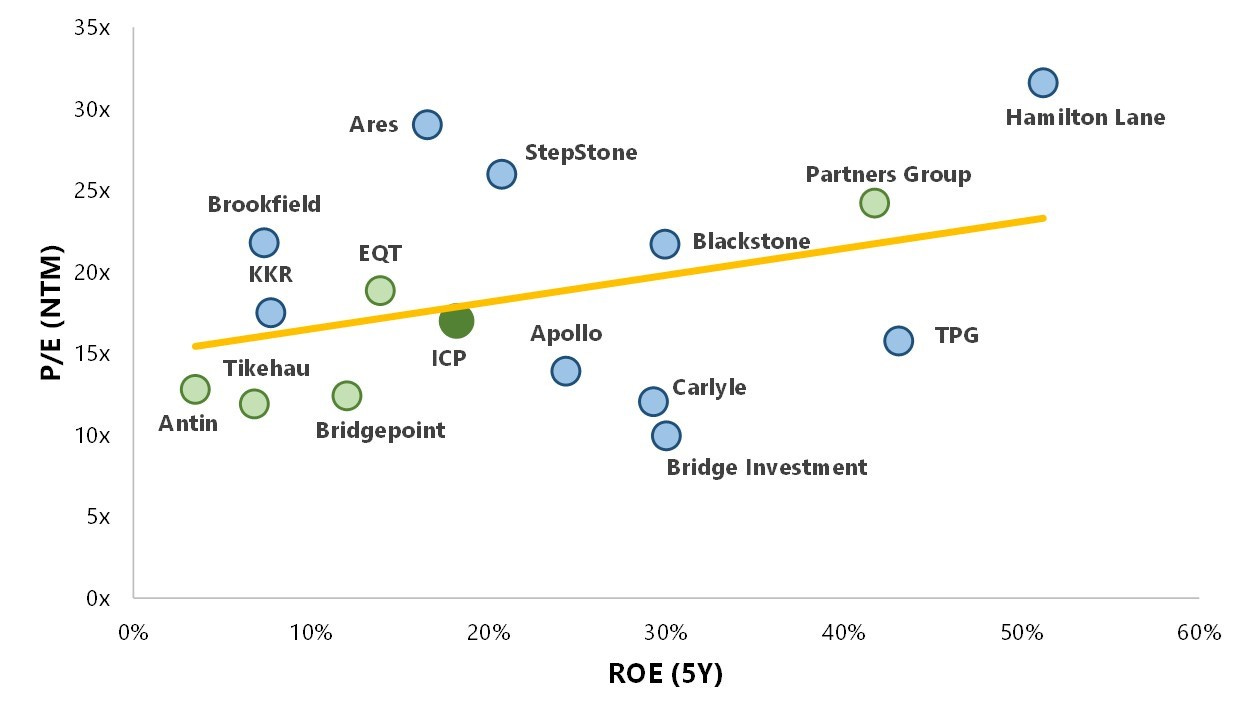

Charting alternative asset managers on basic multiples is not an easy task, as metrics like AUM, ROE, distributable earnings, … vary according to each capital structure and business model (for example, total vs. fee-paying AUMs, the presence of a captive insurance arm, …).

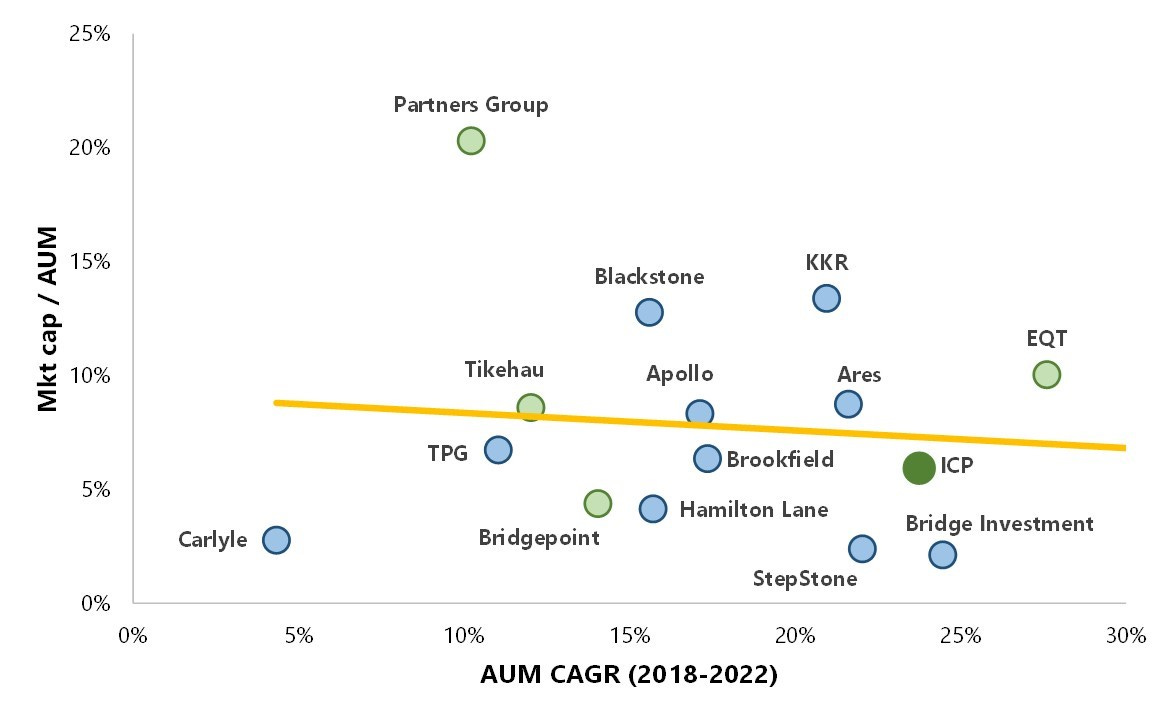

Below, I tried two measures: 1) Market cap as a percentage of AUMs vs recent AUM growth, and 2) 2023e P/E vs 5Y ROE. [Not included in the charts: Blue Owl/Petershill (focused on GP solutions) and 3i Group (only manages its own capital)

On these VERY SIMPLIFIED metrics, ICP appears to be between fair valued and slightly cheap (despite an attractive positioning and excellent AUM growth) compared to its peers.4

Valuation in the asset management space vary a lot: “platforms” trade at higher multiples because of higher growth, more consistent earnings, and better profitability:

Positive net flows

Permanent capital

Operating scale

Management fees vs. Performance fees

Investment income

Profitability margins

ICP publishes regularly a full set of market consensus data: while it does not provide an estimate for EBITDA, for FY24 it can be inferred working up from Group Profits Before Taxes at around £400 million. Using the average EV/EBITDA for Alternative/Private Markets Managers from the chart above (13x-14x: StepStone, probably the closest to ICP for type of business and size, trades at 16x)5, we can estimate ICP’s EV to be around £5.2bn-£5.6bn. Take out around £700 million in net debt and the estimated equity value is £4.5bn-£4.9bn (or between £15.5 and £16.9 per share, an upside of 13%-24% from current prices).

In terms of transactions, there has been a flurry of deals in recent months, especially in the private credit space:

Generali acquired Conning (US$157 bn in private credit)

Man Group acquired 73% of Varagon Capital Partners (US$12 bn in private credit): in total, target’s equity was valued at around US$380 million, equivalent to 3.2% of AUMs

Mubadala Investment Corp, which already owned 10% of Fortress Investment Group, bought out the 90% owned by SoftBank: financial terms were not disclosed, but SoftBank paid $3.3bn for Fortress in 2017 (around 9% of AUMs at the time)

TPG acquired Angelo Gordon (US$73bn in private credit and real estate) for $2.7 bn, or 3.7% of AUMs

PGIM acquired Deerpath Capital Management (US$5 bn in private credit)

Sound Point Capital Management acquired Assured Guaranty (US$15 bn in CLOs)

FS Investments acquired Portfolio Advisors (US$38 bn in a range of private assets)

Nuveen acquired Arcmont Asset Management (US$21 bn in private credit with a focus on Europe): price paid was over $1bn, or 4.8% of AUMs

Being private transactions, most deals did not disclose many details on the acquisition price: where they did, equity valuations were in the 3% to 5% range of AUMs (with the exception of Fortress in 2017, but Softbank is known for over-paying for assets). ICP is currently trading at a market cap of 6% of total AUMs: track record, profitability and size are quite important in these deals (it’s dangerous to just extrapolate from a sample of transactions), but based on this very crude metric it’s difficult at the moment to expect someone to pay much of premium to (potentially) acquire the entire company.

Summing it all up

ICP is very much under the radar (rarely discussed in the press, blogs or conferences), but it’s one of the fastest growing players in an attractive industry.

Following the 2008 financial crisis, it decided to become primarily a capital-light asset manager of third-party AUM, a choice in stark contrast to fellow London asset manager 3i Group which went the opposite way.6

On the plus side:

Big enough to be a safe choice for LPs, but still “small” to have many years left of double-digit AUM growth

Exposure to Europe and an excellent reputation in the region, which is less mature than the US - especially in private credit - and also for LP’s allocations

Current earnings potential is masked by the recent performance of the IC segment: recurring fees are more predictable in nature than gains on investments

With significant AUMs, no controlling shareholders and a still accessible market cap, ICP could be an interesting target for an acquisition: probably not for the giant alternative asset managers (they already have the same capabilities in-house), but maybe for an insurance company looking to add some good long-term strategies to its product offering (exactly what Generali did with Conning)

It also sports a good dividend yield of ~6%

On the negative side: it seems fairly valued (not extremely cheap), so future returns will come mostly from the underlying growth, not from a significant re-rating. The biggest risk is of course that ICP’s funds perform poorly going forward, which will be a double whammy: gains in IC will be lower, and it will be more difficult to attract new funds in FMC.

The long-term trend for private markets appears to be still positive, although there might be volatility in new fundraising in the short- to medium term. And competition is increasing: it’s no longer just few private equity guys extending their reach to other corners of the private assets industry, today almost all large, global traditional asset managers have built their private debt capabilities.

Despite this, I think that private credit in particular still has legs to go: there is a wall of maturities coming up in the next 2 years in many corners of the corporate markets (according to M&G Investments, US$127 bn, 12% of the market’s outstanding debt, in the US HY space, and €97 bn - 23% of the index - in Europe). Most companies will not have problems refinancing in public markets, but some might need to search for alternatives, and it’s not going to be with banks. Plus, with yields now much more interesting than a couple of years ago, LPs are likely to prefer more “conservative” strategies (i.e., private credit rather than private equity) as they do not need to take as much risk to get decent (expected) returns.7

The overall message, however, is that ICP will remain a mid-market provider of capital (a ”niche” where reputation and relationships are especially important for sourcing deals): you won’t find them in a bidding war for Qualtrics at US$12 billion or similar transactions. At current rates, mid-market lending can easily earn a 14%-15% ROE with minimal leverage.

PS: another personal opinion: the more I study alternative asset managers, and the more I’m convinced that you don’t get rich by investing in alts balance sheet, but rather collecting the fees that alts generate. Again, it’s wrong to generalise (the structures, management teams, incentives, … can be very different, and ICP is probably among the good guys), but almost no one got rich investing in hedge funds or mutual funds: rather, hedge funds/mutual funds managers got very wealthy.

In a broader sense the list could also include Ashmore (focus on emerging markets) and Sofina (which has a significant venture capital component). As at the date of writing, VNV is down -47% since publication of its post, Petershill is down -22% and BGLF is down -16% (price aligned with the “real” NAV).

I’ll be using the market ticker, ICP, rather than the ICG acronym in this post

IC also supports a number of costs, including for certain central functions, a part of the Executive Directors’ compensation, and the portion of the investment teams’ compensation linked to the returns of the balance sheet investment portfolio.

Also: ICP’s earnings do not include any funky adjustments for stock compensation, expenses related to new funds, deferred placement fees, acquisition-related expenses, etc. US alternative asset managers calculate adjusted EPS much more aggressively.

Different providers have (sometimes very) different values for these multiples, highlighting again how difficult it is to compare these companies on simple metrics.

From a pure shareholder’s point of view, I personally think that 3i’s structure is preferable. Its model was previously to raise limited-life private equity funds to invest alongside its own balance sheet but is now more similar to a holding company. After a near-death experience during the global financial crisis (due to a combination of debt at both the holding-company level as well as investee-company level), 3i has eschewed raising any more third-party funds. If it is an above-average investor (an important caveat), the company realised that it should generate a better return for its shareholders by earning a multiple on its own capital rather than clipping a fee on the profits enjoyed by investors in funds it managed. Deploying permanent capital also has other structural advantages: not only does it avoid the risk of procyclicality, whereby funds are raised and investments are made when markets are hot and prices are high, but also its unlimited time horizon means it is not compelled to sell investments at the end of a fund life even when the opportunity remains to continue to compound growth for years into the future.

Yields on BBB corporate bonds now exceed the expected earnings yield of the S&P 500 for the first time since 2009: for pension funds "targeting on average around 7%-8% annual returns" these higher corporate bond yields "offer a less risky way" of hitting the target vs stocks (source: Citi)